On Tuesday, August 5, 2025 at 6pm there will be recognition by the O’Fallon Historic Preservation Commission that Sage Chapel Cemetery is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The plaque presentation will take place at the O’Fallon City Hall at a regular meeting of the O’Fallon Historic Preservation Commission.

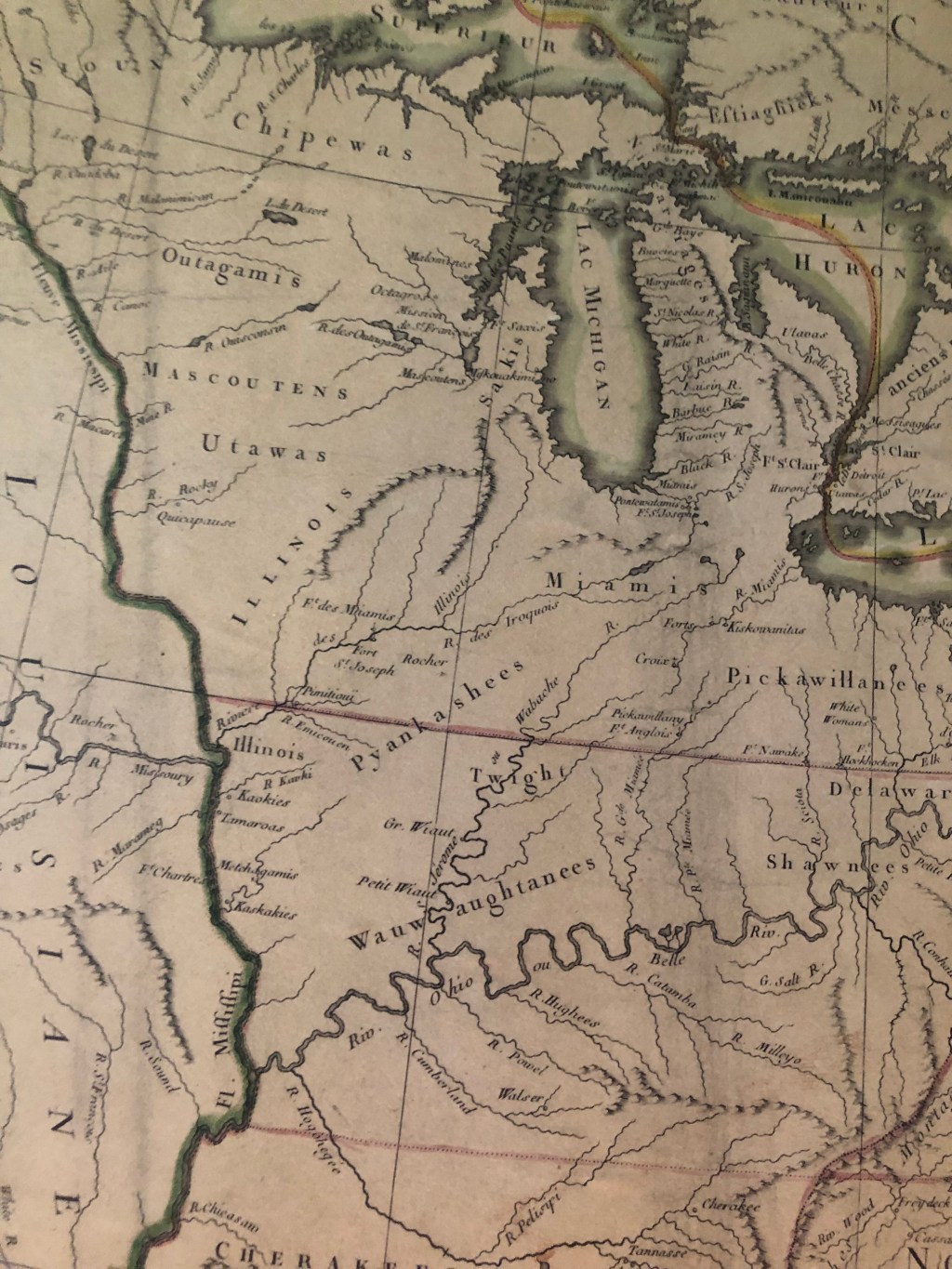

In the early 1800s, Samuel Keithly (1789-1870) came from Kentucky, and settled in St. Charles County, bringing his slaves. The father of a large family with seven children, several step-children, and many grandchildren, the family had other members who owned slaves as well. By the 1840s, the family owned hundreds of acres of land, and had purchased land near today’s O’Fallon, Missouri where Sage Chapel Cemetery lies.

Among Samuel Keithly’s slaves was John Rafferty. According to Mary Stephenson, a descendant, John and his sisters, Frances, Ludy, Elsie, and Lizzie had been born in Kentucky, and brought to Missouri.When John Rafferty (Senior) passed away in 1881, his former master Samuel Keithly (Senior) had already passed away as well. Burials had already been taking place on the former Keithly plantation, on land that had been inherited and was by then owned by his daughter Mahala Keithly Castlio (1817-1896) and her husband Jasper N. Castlio.

So on August 20th, in 1881, Mahala and her husband Jasper, transferred to three Trustees of the African Methodist Church, namely John Rafferty’s close friend Walter Burrel, Joel Patterson and Taylor Harris, for the use of the preachers of the African Methodist Episcopal Conference (headed by St. John’s A.M.E. Church in St. Charles Missouri) one acre of land, which became known as Sage Chapel Cemetery, so that these African-American burials could continue to take place. That same deed conveyed a half acre (with a building) to be used as a church. Then former slaves, like John Rafferty and Charles Letcher could continue to be buried where their ancestors had already lain for decades.

The A.M.E. Church had a traveling Pastor, Jefferson Franklin Sage, who would visit all of the town’s along this route between St. Charles and Jonesburg at the Warren/MontgomeryCounty line, which was perhaps one reason why the little church became known as Sage’s Chapel. It has also been said that the Cemetery was referred to as Sage Chapel because the field that they liked to worship in was filled with Sage. Sage is used in many cultures to worship.

By the early 1900s, the early road to St. Peters, which led from the railroad in O’Fallon, passing Sage Chapel Church and the cemetery, became known as “the Hill” because of the African-American community that lived along it. There was the Thornhill house where the colored members of the Oddfellows met, the black school house, and two other African-American churches. Next to the school was Cravens Methodist (Northern) and further down near the creek was the Wishwell Baptist, which was a plant of Hopewell Baptist near Wentzville. Many of those buried at Sage Chapel Cemetery were members of one of those three churches or of that community, that is today’s Sonderen Street.

By the late 1940s, many of the African Americans were moving away from O’Fallon in search of employment. The three churches would close, and have since even disappeared entirely, along with any records that may have existed. But the cemetery remains, as a testament to the African American community thanks to the efforts of the Hayden family. They and others would maintain and care for the cemetery for many years. By the beginning of the 21st Century though, that was becoming increasingly difficult. Then members of the community came together with renewed efforts to increase the awareness of the cemetery, and what a special place Sage Chapel Cemetery is.

Today, the cemetery is owned and maintained by the City of O’Fallon and has 117 documented burials of which only 37 have headstones (2018). Of those documented burials at least 17 of them were individuals born enslaved. They personally experienced Emancipation Day for Missouri’s slaves on January 11, 1865. Many of these people had difficult lives and would experience segregation their entire lives. The story of the people of Sage, tells us of a time period that today’s living cannot recall. Oral family histories continue to share stories of these people’s lives, and their tragic deaths. Sage Chapel Cemetery is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. This website shares the stories of the “People of Sage” who lie buried there because “As long as a name can be spoken, that person shall not be forgotten.” And it is only through a recognition of that past, that we can continue to build a better future for all generations to come.

Here is a PDF you may download. Sage Chapel Cemetery Nomination – Final Sage Chapel Cemetery Cemetery was officially listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2018. The Cemetery is located at 8500 Veterans Memorial Parkway.

Here is a link to the list of all the people who we know to be buried in this almost forgotten cemetery.

You must be logged in to post a comment.