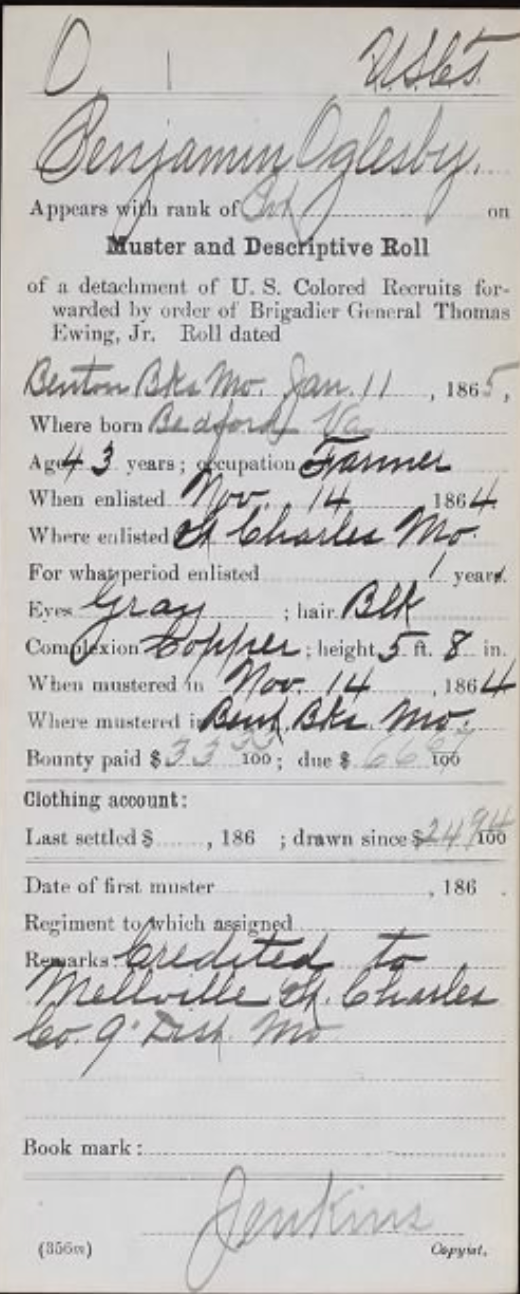

Several men, including Benjamin Oglesby, for whom St. Charles County Park Oglesby Park is named, served in the U.S. Colored Troops. Oglesby served in the 56th. There are still many families whose families served in the U.S. Colored Troops during the Civil War…

The War Department issued General Order #143 on May 22, 1863, to facilitate the recruitment of African-American soldiers to fight for the Union Army. The US. Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act in July 1862, which freed slaves whose owners were in rebellion against the United States, and the Militia Act empowered the President to use free blacks and former slaves from rebels states in any capacity in the army. President Lincoln was concerned that the four border states, of which Missouri was one. Lincoln opposed early efforts to recruit black soldiers, although he accepted the Army using them as paid workers. Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation on September 22 announcing that all slaves in rebellious states that had seceded would be free as of January 1. Recruitment of colored regiments began in full force following the Proclamation in January 1863.

Approximately 175 regiments comprising more than 178,000 free blacks and freedmen served during the last two years of the war. Their service bolstered the Union war effort at a critical time. By the war’s end, the men of the USCT made up nearly one-tenth of all Union troops. The USCT suffered 2,751 combat casualties during the war, and 68,178 losses from all causes. Disease caused the most fatalities for all troops, both black and white. In the last year-and-a-half approximately 20% of all African Americans enrolled in the military lost their lives. Notably, their mortality rate was significantly higher than white soldiers.

Before the USCT was formed, several volunteer regiments were raised from free black men, in the South. The first engagement by African-American soldiers against Confederate forces during the Civil War was at the Battle of Island Mound in Bates County Missouri on October 28–29, 1862. African Americans, mostly escaped slaves, had been recruited into the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteers. They accompanied white troops to Missouri to break up Confederate guerrilla activities based at Hog Island near Butler, Missouri. Although outnumbered, the black soldiers fought valiantly, and the Union forces won the engagement. The conflict was reported by Harpers Weekly. There were 114,931 enslaved men, and 3,572 freedmen in Missouri, yet there were 8,344 men who enrolled.

After considerable foot-dragging, General John Schofield finally allowed the recruitment of Missouri slaves into the Union Army. The first regiment began to take in recruits in June 1863 and was finally organized in August. To sooth the political feelings of proslavery Unionists in the state and at the request of Missouri’s Provisional Governor, Hamilton Gamble, the new regiment was designated the 3d Arkansas Infantry, African Descent, even though its soldiers were Missourians. Schofield ordered that slaves who were accepted for the army be given a certificate declaring that they were forever free. To placate their owners – at least those who were loyal – the government would allow them to claim $300 per man who were successfully mustered into service. Schofield did not, however, initially permit recruiting officers to travel to the field for men. Rather, they were directed to set up offices in the towns. That meant that slaves who wished to join had to run away from their masters (or seek their consent). Contrary to standing orders, slave patrols were revived in some counties for the express purpose of preventing bondsmen from enlisting. Some slaveholders sought to evade recruiters by selling their slaves to persons in Kentucky until the practice was outlawed in March 1864.

On Jan. 7, 1864, the St. Charles Cosmos newspaper reported

“The Corps D’Africque, George H. Senden is making commendable progress in his task of enlisting American soldiers of Aftican descent to help fight the great battle against slavery. Notwithstanding the intense bitter and most intolerable cold of New Years, and the days that followed it, he has enlisted some thirty-two “swarthy sons of toil, who are willing to peril their lives for freedom, and the prospects are decidedly favorable for many more.

Owners, if they could prove their loyalty, received $300 for each slave enlisted. The men received $10 per month – $3 less than white troops – and their officers were allowed to withhold $3 a month for clothing, a charge not levied on white troops. At the time the blacks were enlisting, white troops who volunteered received bonuses of $302 to $402.

The regiment was redesignated as the 56th U.S. Colored Troop Infantry on March 11, 1864, as part of the general reorganization of black regiments in the Union Army. Its first commander was Col. Carl Bentzoni, a Prussian-born sergeant in the 1st U.S. Infantry of the Regular Army prior to his assignment to command black troops. The 56th USCT remained on post and garrison duty at Helena. A member of Company G was its First Sergeant, James Baldwin (also sometimes rendered Balldon). He claimed to have escaped from a slave owner named Joseph Montgomery. Montgomery was a Natchez merchant and the owner of 180 slaves. Baldwin made his way to Helena, and was apparently sent to St. Louis in 1863 by the General Benjamin Prentiss, then the commander in eastern Arkansas. He joined the Third Arkansas in the summer of 1863. (After the war, a William Dunning from Buchanan County (St. Joseph) said that Baldwin’s name was actually Willie or Willis and previously belonged to him.) Baldwin was evidently very intelligent and reliable, for he held the post as the top enlisted man in the company

Some of the masters and mistresses treated soldiers’ wives and children badly. For example, Private Andrew Hogshead received a letter from his wife Ann that read, “You do not know how bad I am treated. They are treating me worse and worse every day. Our child cries for you. Send me some money as soon as you can for me and my child are almost naked. My cloth is yet in the loom and there is no telling when it will be out. Do not send any of your letters to Hogsett [her owner] especially those having money in them as Hogsett will keep the money.” A Union officer reported that wives of Simon Williamson and Richard Beasley “have again been whipped by their Masters unmercifully.” Their owner tried to prevent them from going to the post office to pick up mail and if they did get mail, the master was “sure to whip them for it if he knows it.”Lieutenant William Argo wrote from Sedalia that the families of black soldiers were being driven from their masters’ homes. He was directed to send them to a contraband camp at Benton Barracks in St. Louis. In the first three months of 1864, the camp received 947 men, women and children; 330 left on their own; 234 were hired out to “loyal responsible persons”; 101 died; and 268 remained – 165 in the hospital.

In August 1863, about five hundred men under Major Moses Reed embarked on the steamboat Sam Gaty for Helena, Arkansas, a town that would be their duty station for the next three years. The rest of the regiment arrived in February 1864. Helena was captured by Union troops in 1862. Almost immediately, slaves began to flock there. After the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, literally thousands arrived. Conditions at Helena were atrocious. Former slaves sought shelter in abandoned buildings, barns, caves, discarded tent, brush shelters, and rude huts in an area called “Camp Ethiopia.” Helena’s commander was “at a loss to know what to do with them.” By the summer of 1864, there were 3,300 black civilians living in the town.

Helena Arkansas Helena, Arkansas had been captured by Union troops in 1862. -The 56th’s experience proved the city to be one of the unhealthiest spots on the Mississippi. Overall, in its three years there the regiment lost about 500 men to disease – typhoid, malaria, chronic diarrhea (probably dysentery), smallpox, measles, and cholera.For the most part the regiment performed mostly boring garrison duties. They maintained forts and guarded warehouses. A few hundred men were sent downriver to Island No. 63 to protect a woodyard that supplied fuel for steamboats. Conditions at Island No. 63 were no better than Helena, and several men died there of various diseases.

They would also see Action at Indian Bay April 13, 1864 Then at. Muffleton Lodge June 29. They were on Operations in Arkansas July 1-31. . On July 26, 1864, near Wallace’s Ferry in Arkansas, the unit (now re-designated as the 56th United States Colored Infantry Regiment), along with the 60th Colored Infantry regiments and Battery E of the 2nd U.S. Colored Artillery were attacked by a superior force of Confederate cavalry commanded by Col. Archibald S. Dobbins. Supported by about 150 men from the 15th Illinois Cavalry, the infantry regiments organized a fighting retreat and at a crucial moment in the battle made a counter charge into the enemy line. The unit was praised by the commander of Battery E in his after action report.

HDQRS. BATTY. E, SECOND U.S. COL. ARTY. (LIGHT), Helena, Ark., July 29, 1864.

SIR: I have the honor to report that on the evening of July 25, at 4.30 p.m., in company with Colonel Brooks, of the Fifty-sixth U.S. Colored Infantry, in command of detachments from the Fifty-sixth and Sixtieth U.S. Colored Infantry, with one section of Battery E, Second U.S. Colored Artillery (light), commanded by Capt. J. F. Lembke, we moved out on the Little Rock road with orders to guard the crossing at Big Creek, eighteen miles from this place….Colonel Brooks with part of the infantry crossed over to make a reconnaissance. In less than an hour he returned, reporting no enemy in that vicinity, and at once ordering the force left in the rear forward, and that breakfast be got and the teams watered and fed. Before the teams were all un-hitched it was rumored that the enemy was advancing upon our rear. I at once got the rifled gun into position about 200 yards from the creek and facing our left, and awaited their approach. The enemy were concealed in the thick timber and were within 150 yards of us before I opened on them, when they charged with a yell, but being well supported by Captain Brown, of the Sixtieth, with sixteen men, and Captain Patten, of the Fifty-sixth, with twenty-five men, and using canister rapidly and carefully, we repulsed them….

During the whole fight the colored men stood up to their duty like veterans, and it was owing to their strong arms and cool heads, backed by fearless daring, alone that I was able to get away either of my guns. They marched eighteen miles at once, fought five hours, against three to one, and were as eager at the end as at the beginning for the fight. Never did men, under such circumstances, show greater pluck or daring.

I am, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

H. T. CHAPPEL,

First Lieutenant.

Colonel Brooks of the 56th was mortally wounded early in the action and Lieutenant Colonel Moses Reed assumed command. The 56th and the other Union forces made their way back to Helena. Union casualties in the battle were 19 killed, 40 wounded, and four missing. Confederate losses are unknown. Colonel Brooks was replaced by Colonel Charles Bentzoni in January 1864. Bentzoni was born in Prussia. He served in the Prussian and British Armies before enlisting in the regular army in 1857 at the age of twenty-seven. A sergeant at the beginning of the war, he was commissioned in the Eleventh United States Infantry Regiment in November 1861. He spent most of the war at Fort Independence in Boston Harbor training recruits. He finally made it to the battlefield and fought with distinction, receiving a brevet captaincy for gallantry at the Battle of Peebles Farm (or Poplar Springs Church) on September 30, 1864, as part of the siege of Petersburg. One of his fellow officers in the Eleventh Infantry was John Coalter Bates, the son of Edward Bates. (The younger Bates stayed in the Army and retired as a Lieutenant General in 1906 after serving as the Army’s Chief of Staff.) [i] “I have evidence that the enemy murdered in cold blood three wounded colored soldiers who were left on the battle-field on the 26th ultimo, and that yesterday they murdered two which they found at the plantations unarmed.”

In his official report, Brigadier General Joseph O. Shelby, C.S. Army, who was the superior of Colonel Dobbins provided this summary:

“Colonel Dobbin and Gordon, immediately after their fight of July 26, made a forced march upon the Federal plantations near Helena and harried them with a fury greater than a hurricane. They captured 200 mules, 300 negroes, quantities of goods and clothing, and killed 75 mongrel soldiers, negroes and Yankee schoolmasters, imported to teach the young ideas how to shoot.”

Bentzoni and the Fifty-Sixth helped two Quakers from Indiana, Alida and Calvin Clark, move an orphanage and elementary school for blacks away from disease-infested Helena to a more healthful site nine miles northwest of town. The Clarks expanded this institution into what became Southland College, the first academy of higher learning for African Americans west of the Mississippi. Bentzoni also attempted to protect freedmen from exploitation by their former owners and “other evil-disposed persons.” He ordered that such miscreants be brought before military commissions for keeping their former slaves “restrained from their liberty” and violating contracts of employment entered after the slaves were freed by the Emancipation Proclamation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.