The entire United States is about to celebrate our Nation’s 250th Anniversary. And we are part of that history. The earliest settlement north of the Missouri River and west of the Mississippi River, was a tiny village that became known as Saint Charles. Founded on the banks of the Missouri River, amongst the Osage, was Louis Blanchette’s fur trading post in 1769. While he was a French-Canadian fur trader, under Spanish rule, others soon arrived. Before being acquired in the Louisiana Purchase, the great trailblazer Daniel Boone, a Revolutionary War veteran himself arrived with a lot of friends and followers. With Boone came thousands from the eastern states of Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee with their enslaved. By the time Lewis and Clark passed through with their Corps of Discovery, there were over 100 families living there along our historic Main Street already. Everything since 1769, is part of our “history”. Let’s celebrate!

ST. CHARLES COUNTY HISTORY

By Dorris Keeven-Franke

-

-

Campbell is still waiting for the heavy wagons to catch up to him. The household goods will be loaded on a flat bottomed Keelboat to be shipped up river. The whole caravan can then move faster.

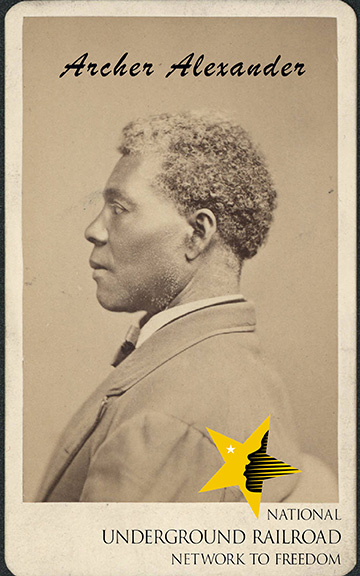

The Journey continues… This is the journal of William Campbell, leading four families, Alexander, McCluer, Wilson and Icenhower from Lexington, in Rockbridge County, Virginia to Dardenne Prairie, in Saint Charles County Missouri. It includes at least 25 enslaved people, including the enslaved Archer Alexander, who today is found on Washington, D.C.’s Emancipation Monument. The journal is located in the Leyburn Library, Special Collections and Archives, located at the Washington and Lee University, in Lexington, Virginia. They had departed Lexington on August 20, 1829… Campbell has spent the past five days in Charleston, (West) Virginia waiting on the wagons that are loaded with household goods to catch up to him in Charleston.

To continue to follow the journal of William Campbell, his next entry is September 5th. You can follow him here at this link…https://archeralexander.blog/2023/09/05/5-september/ where the journal picks up again.

Written in 1829, this is the journal of William M. Campbell. This is also the story of Archer Alexander, an enslaved man born in Lexington, Virginia, who was taken to Missouri in 1829. There are 38 entries in Campbell’s journal, which begins on August 20, 1829 that you can read and follow the story of Archer Alexander. Campbell’s journal is located in the Archives at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia and is being shared here so that we may hear all the voices, including those whose voices were not shared originally. The photos were taken by me when visiting Virginia for research and then following the pathway that Campbell shares in his journal. Please keep in mind the context of the time in which this journal was written. Feel free to share your comments directly on this blog or join in on the discussion in the St. Charles County History Facebook Group. You may sign up for email alerts of the daily blog posts below.

-

There is no entry by Campbell on August 30th

The confluence of the Kanawha and Elk Rivers made Charleston a great location to stop and rest. Apparently William Campbell had ridden way ahead in his buggy. Campbell had left Lexington on the 20th of the August and traveled approximately 210 miles. Campbell had also made this journey before, and most probably Robert Cummins, had as well, as he had invested in property in Missouri before statehood. Cummings was most likely staying with the slower wagons. Twenty-four year old Campbell, who had studied law at Washington and Lee University makes friends easily.

The confluence of the rivers would allow them to ship their furniture, and household goods on ahead, thereby allowing them to travel easier and faster. The boat, called a keelboat, is essentially a large flat bottom boat used for these purposes. Not designed for passengers, it was more like a barge. Perhaps Cummings was then assigned the task of staying with the goods, that were being shipped on ahead. This was a common practice, whether coming from the north down the Ohio River from ports like Baltimore, or from the southern regions. This would allow for much easier travel. Sunday was a day of rest, and most likely the Alexanders, McClures and Icenhower would have visited the Presbyterian church in the city.

Written in 1829, this is the journal of William M. Campbell. This is also the story of Archer Alexander, an enslaved man born in Lexington, Virginia, who was taken to Missouri in 1829. There are 38 entries in Campbell’s journal, which begins on August 20, 1829 that you can read and follow the story of Archer Alexander. Campbell’s journal is located in the Archives at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia and is being shared here so that we may hear all the voices, including those whose voices were not shared originally. The photos were taken by me when visiting Virginia for research and then following the pathway that Campbell shares in his journal. Please keep in mind the context of the time in which this journal was written. Feel free to share your comments directly on this blog or join in on the discussion in the St. Charles County History Facebook Group. You may sign up for email alerts of the daily blog posts below.

Photo by Dorris Keeven-Franke 2019

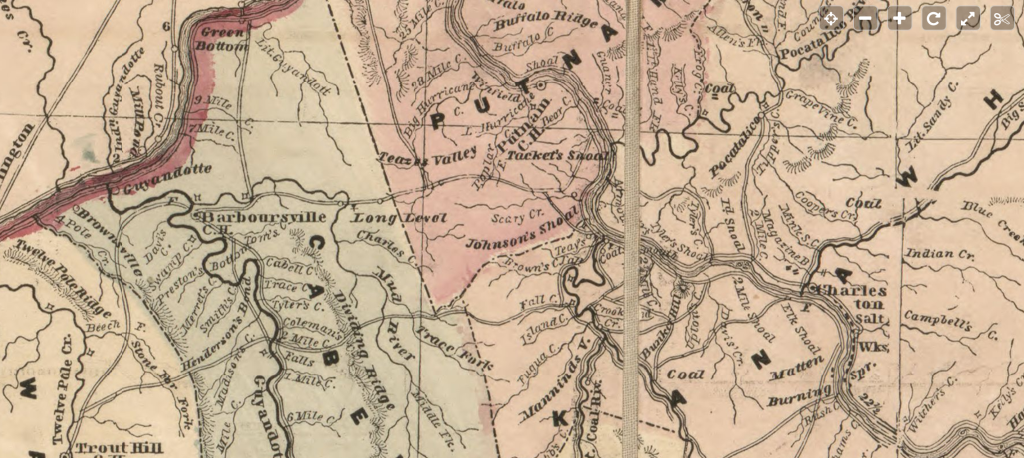

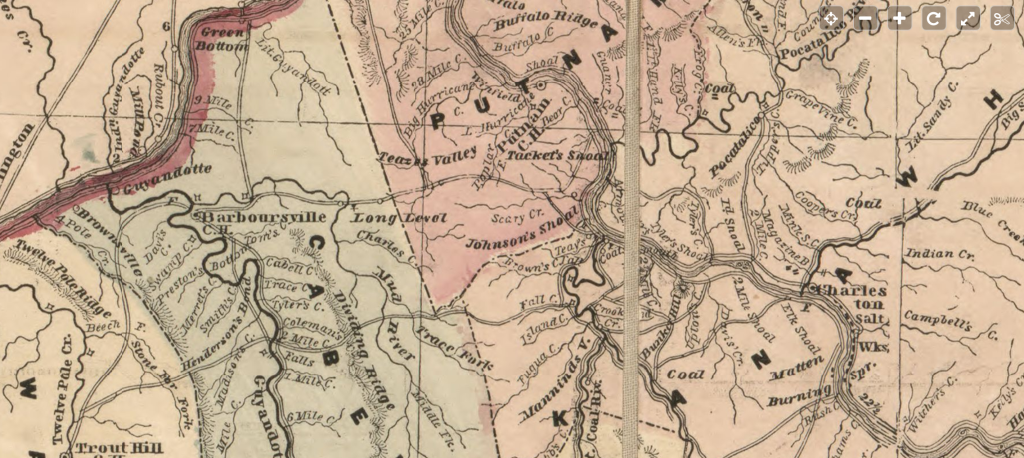

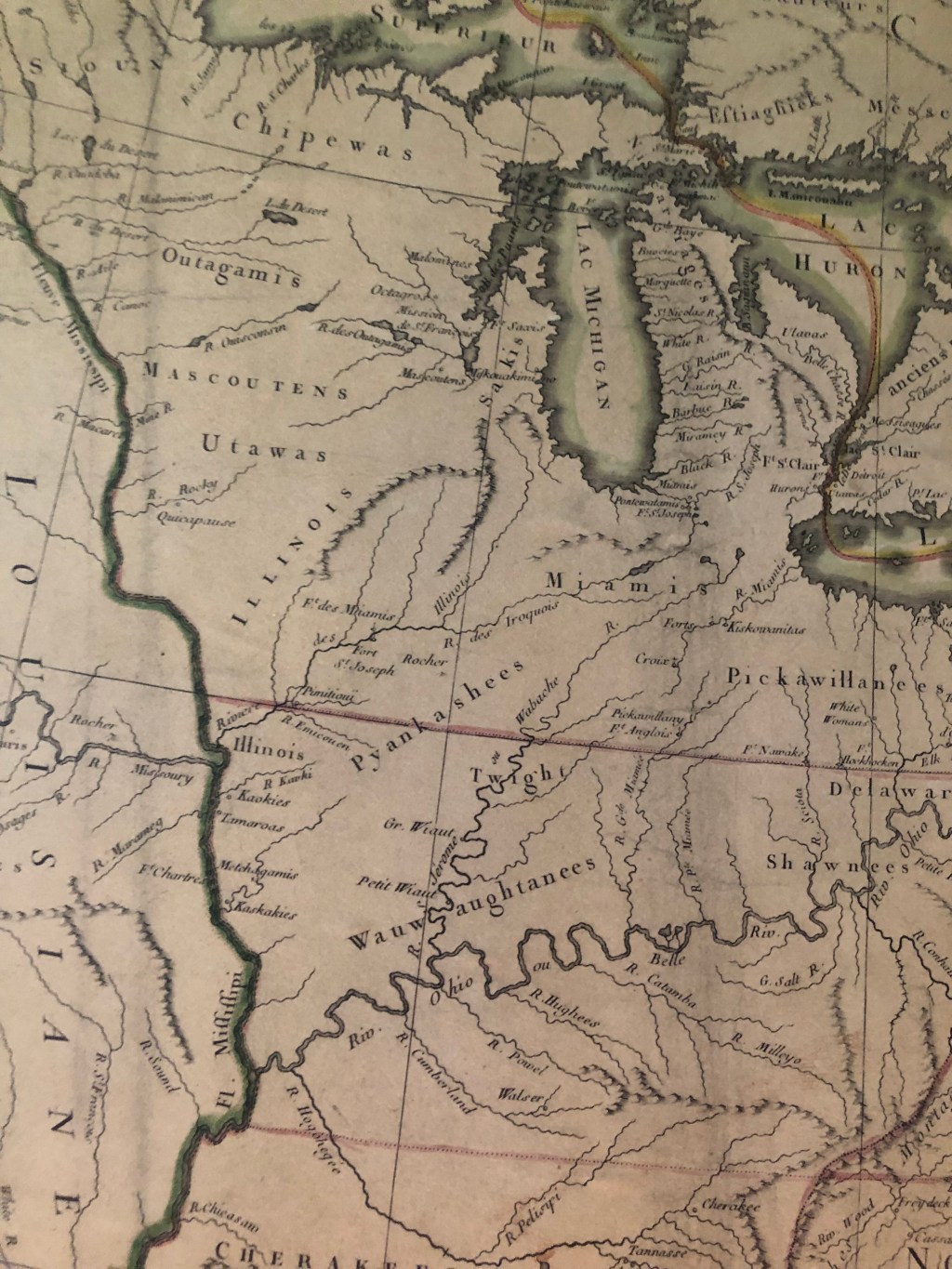

Lloyd’s official map of the state of Virginia from actual surveys by order of the Executive 1828 & 1859 from the Library of Congress

-

29 August , 1829 – We waited patiently for the arrival of our wagons. In the meantime I became acquainted with a number of the citizens, with whom I was well pleased.

Written in 1829, this is the journal of William M. Campbell. This is also the story of Archer Alexander, an enslaved man born in Lexington, Virginia, who was taken to Missouri in 1829. There are 38 entries in Campbell’s journal, which begins on August 20, 1829 that you can read and follow the story of Archer Alexander. Campbell’s journal is located in the Archives at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia and is being shared here so that we may hear all the voices, including those whose voices were not shared originally. The photos were taken by me when visiting Virginia for research and then following the pathway that Campbell shares in his journal. Please keep in mind the context of the time in which this journal was written. Feel free to share your comments directly on this blog or join in on the discussion in the St. Charles County History Facebook Group. You may sign up for email alerts of the daily blog posts below.

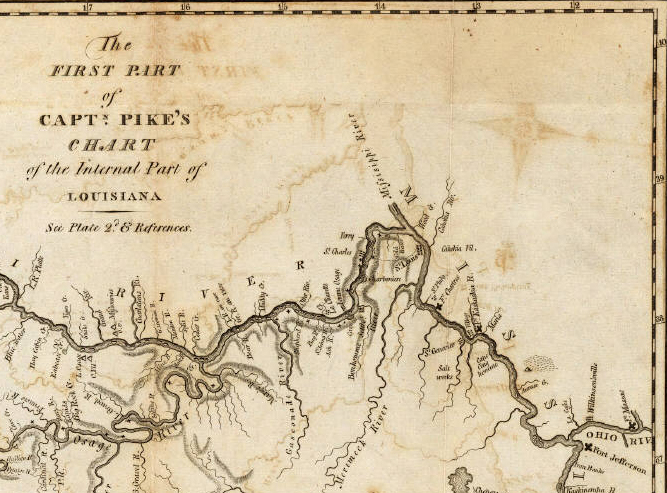

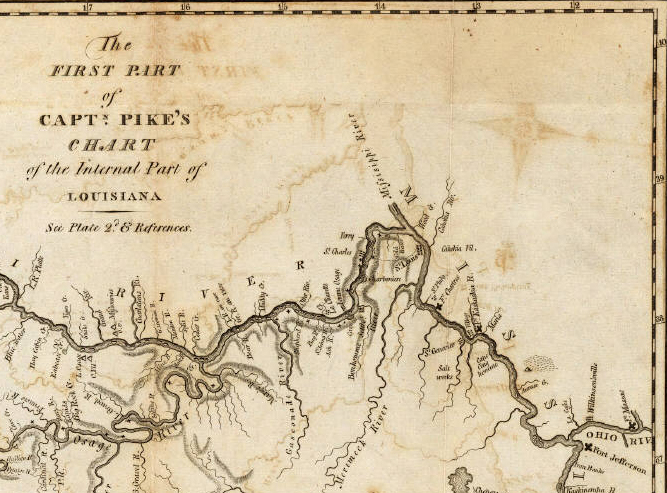

Library of Congress

-

Strayed about town without any acquaintance and all the feeling of a stranger in a strange place.

Written in 1829, this is the journal of William M. Campbell. This is also the story of Archer Alexander, an enslaved man born in Lexington, Virginia, who was taken to Missouri in 1829. There are 38 entries in Campbell’s journal, which begins on August 20, 1829 that you can read and follow the story of Archer Alexander. Campbell’s journal is located in the Archives at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia and is being shared here so that we may hear all the voices, including those whose voices were not shared originally. The photos were taken by me when visiting Virginia for research and then following the pathway that Campbell shares in his journal. Please keep in mind the context of the time in which this journal was written. Feel free to share your comments directly on this blog or join in on the discussion in the St. Charles County History Facebook Group. You may sign up for email alerts of the daily blog posts below.

-

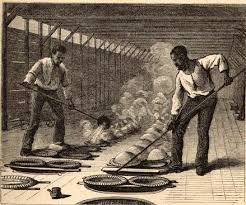

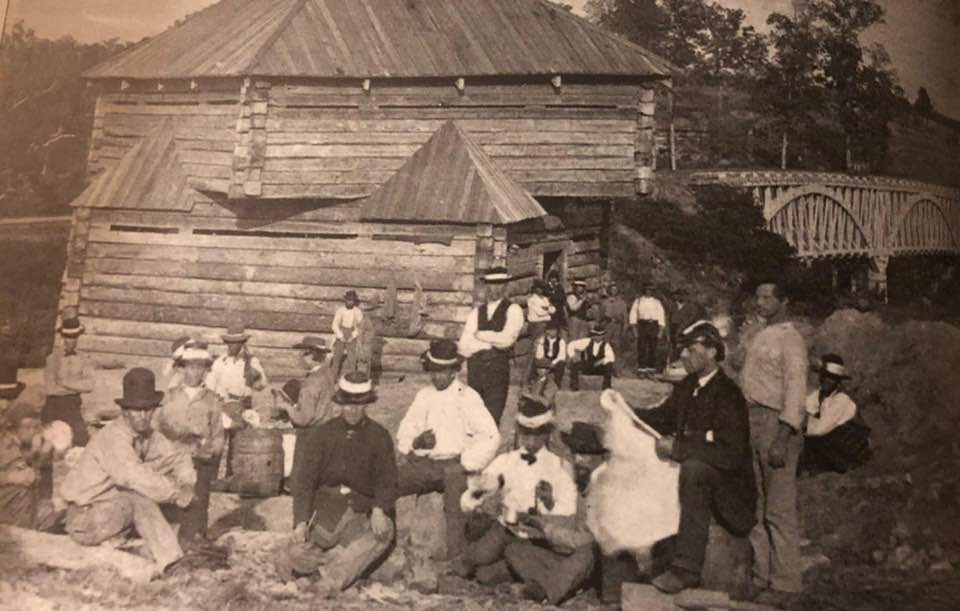

27 August 1829 – Traveled twelve miles to Stockton’s for breakfast, excellent fare. The turnpike ends eight miles from Ganly [Gauley]. A new contract had just been taken by Trimble and Thompson to continue to Charleston, 30 miles at the rate of $1595 per mile, bridges included. Very cheap road. The sixty miles between Charleston and Sandy will be let out on the first of October. We this day passed through the rich narrow bottoms of Kanawha, a great part of which is covered with a heavy crop of corn. Ten miles of the valley are called “the Licks” from their being covered with salt works. There are sixty furnaces which manufacture 2,000,000 bushels of salt annually.* The manufacturing of salt would be much more extensive if it were not entirely monopolized by a company. It will someday be a place of much more importance. The buildings about the salt works are miserable shells and hovels, temporary and unsubstantial. We passed the Burning Springs and came to Charleston about night. Charleston is a town about as large as Lexington, Virginia. It is built on a bottom along the Kanawha River. One street is laid off along the margin of the river, scarcely leaving room for a row of houses between the street and the river; here all the business is done. The other street has but few houses on it. The beauty of the town is very much diminished by the row of houses on the river bank. The houses are principally of wood, some brick.

Written in 1829, this is the journal of William M. Campbell. This is also the story of Archer Alexander, an enslaved man born in Lexington, Virginia, who was taken to Missouri in 1829. There are 38 entries in Campbell’s journal, which begins on August 20, 1829 that you can read and follow the story of Archer Alexander. Campbell’s journal is located in the Archives at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia and is being shared here so that we may hear all the voices, including those whose voices were not shared originally. The photos were taken by me when visiting Virginia for research and then following the pathway that Campbell shares in his journal. Please keep in mind the context of the time in which this journal was written. Feel free to share your comments directly on this blog or join in on the discussion in the St. Charles County History Facebook Group. You may sign up for email alerts of the daily blog posts below.

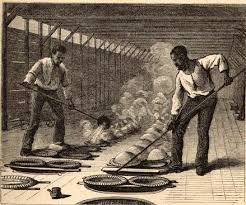

*The Kanawha salt furnaces were labor intensive. The salt makers employed many slaves, making Kanawha County an exception to the fact that Western Virginia had relatively few slaves. By 1850, there were as many as 1,500 slaves at the salt works, owned by the salt barons or leased from other owners. See https://www.wvgazettemail.com/life/historian-shines-light-on-regions-forgotten-history-of-slaves-owners/article_a5dcfb35-fd5f-50c7-9b06-51f456cde046.html

-

Rain – drove on, came to New River, passed along its stupendous cliffs, by a magnificent road, crossed Goly* Bridge, toll $1. This is an open bridge lately erected by B and S. It is built on piers at the same place the Arched Bridge formerly stood. It is an handsome bridge. Two miles below the bridge we passed the great falls of Kenewha*, a great natural curiousity, an admirable site for water works. A great quantity of timber is sawed here and several hundred large flat boats are built here for the purpose of taking salt down the Ohio. Staid all night at Huddleston’s; fared very well. Had a good deal of conversation with the citizens of Ohio, Mississippi and Indiana, who were traveling and had called to stay all night.

Written in 1829, this is the journal of William M. Campbell. This is also the story of Archer Alexander, an enslaved man born in Lexington, Virginia, who was taken to Missouri in 1829. There are 38 entries in Campbell’s journal, which begins on August 20, 1829 that you can read and follow the story of Archer Alexander. Campbell’s journal is located in the Archives at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia and is being shared here so that we may hear all the voices, including those whose voices were not shared originally. The photos were taken by me when visiting Virginia for research and then following the pathway that Campbell shares in his journal. Please keep in mind the context of the time in which this journal was written. Feel free to share your comments directly on this blog or join in on the discussion in the St. Charles County History Facebook Group. You may sign up for email alerts of the daily blog posts below.

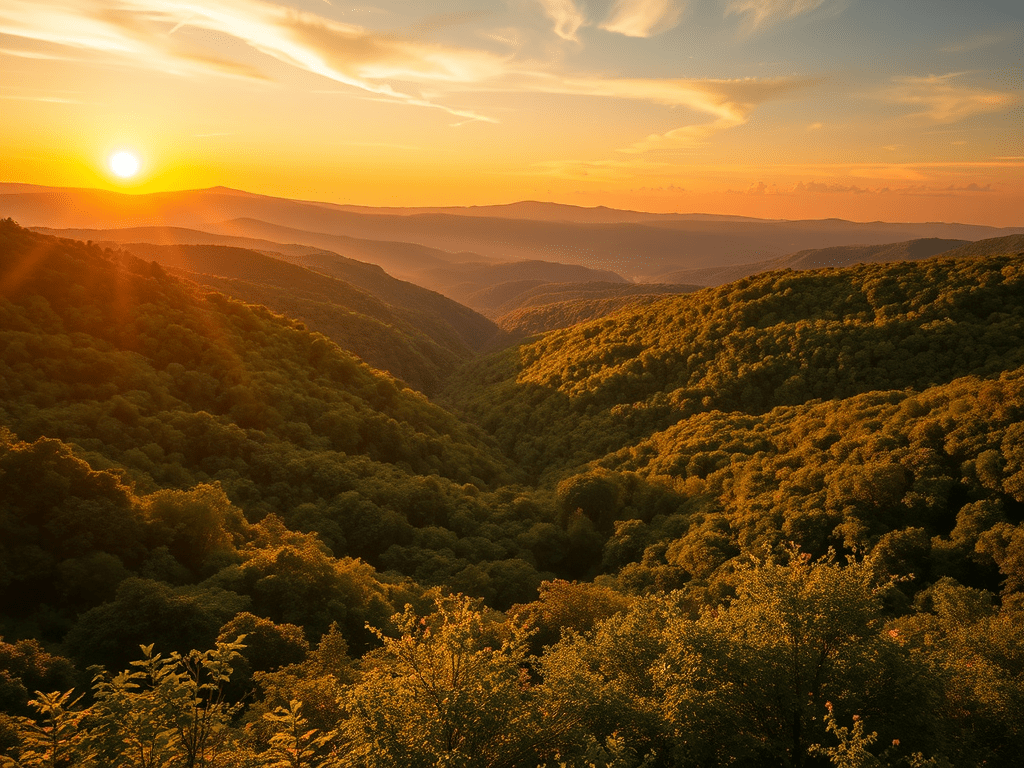

This is one of the most beautiful sights in West Virginia. The wood mills that once made flatboats for travel down the Ohio River are today’s paper mills. The lumber industry fuels the economy. Traveling the side roads such as Route 60, the Midland Trail and a National Scenic Byway one sees so much more history and beauty. Photo by Dorris Keeven-Franke.

-

We entered on a very mountainous region crossed Meadow Mountain, Big and Little Sewell and numerous other ridges, for which the inhabitants say thay cannot afford names. All along these, numerous houses have been built for the purpose fo keeping entertainment. Many of them good houses. Houses are still being built for that purpose and much more land is clearing out where formerly there were no settlements. Staid all night at Tyrees fared well.

Written in 1829, this is the journal of William M. Campbell. This is also the story of Archer Alexander, an enslaved man born in Lexington, Virginia, who was taken to Missouri in 1829. There are 38 entries in Campbell’s journal, which begins on August 20, 1829 that you can read and follow the story of Archer Alexander. Campbell’s journal is located in the Archives at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia and is being shared here so that we may hear all the voices, including those whose voices were not shared originally. The photos were taken by me when visiting Virginia for research and then following the pathway that Campbell shares in his journal. Please keep in mind the context of the time in which this journal was written. Feel free to share your comments directly on this blog or join in on the discussion in the St. Charles County History Facebook Group. You may sign up for email alerts of the daily blog posts below.

From Lexington, Virginia to Lewisburg, today’s West Virginia our travelers have come seventy-five miles through the Appalachian Mountains. First crossing the Blue Ridge Mountains, they have climbed into the Shenandoah valley at the altitude of 2,080 feet. The ages of the members of the caravan range from three-month-old Sallie Campbell McCluer born in May, and Mr. Icenhower’s father-in-law who is over ninety-years old. When they crossed Sewell Mountain they had climbed to 3,212 feet. Anna Icenhower and another member of the enslaved community were several months pregnant.

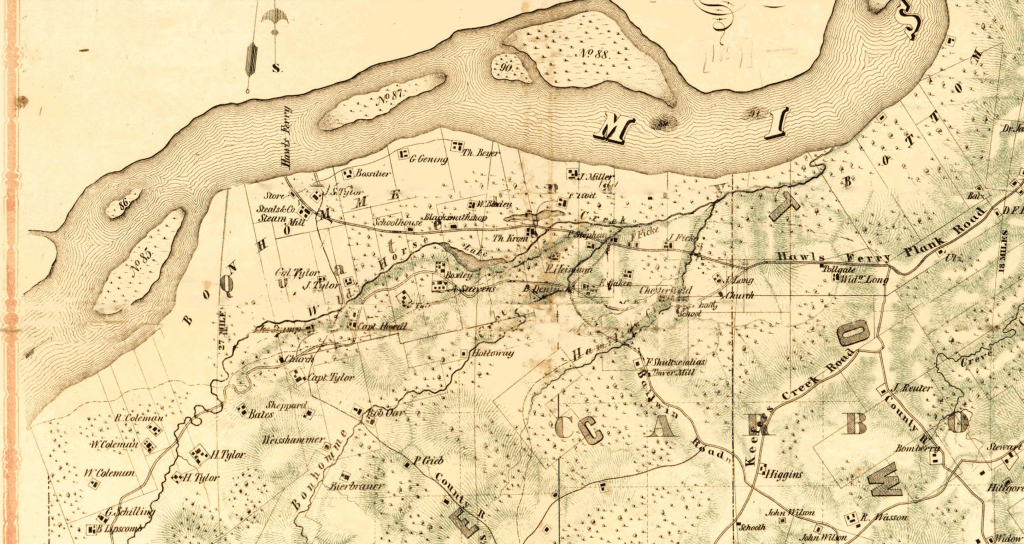

https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3800.fi000077http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3880.rr003100 Library of Congress Maps like the one above were quite useful to the traveler in 1829. Nothing like the Google Maps (see below) we use today. They had no GPS coordinates to insert into an app either. In 1829 roads are dirt, and your mode of transportation determined your speed. A man on a horse could travel much faster than a wagon full of household goods, or one of the enslaved walking alongside. Inns were stopping points that were usually the right distance for a days journey from the last innkeeper. Perhaps Campbell has put up with William Tyree and Innkeeper in today’s Anstead, Fayette County, West Virginia.

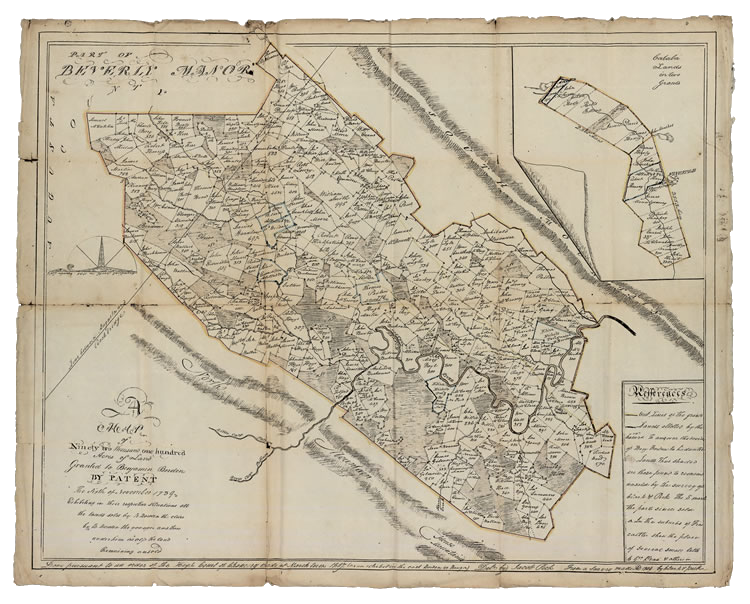

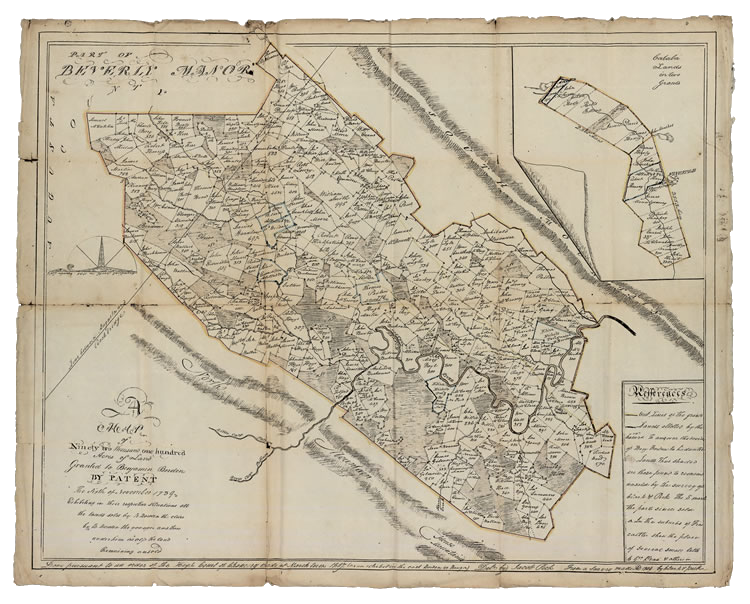

About this map from the Library of Congress

Lloyd’s official map of the state of Virginia from actual surveys by order of the Executive 1828 & 1859.Summary Indicates drainage, state and county boundaries, roads, distances, place names, mills, factories, “places remarkable for military incidents,” and the railroad network.Contributor Names: Lloyd, James T.Fillmore, Millard, 1800-1874, collector. Created / PublishedNew York, 1861.Subject Headings- Virginia–Maps- United States–VirginiaNotes- LC Civil War Maps (2nd ed.), 450- LC Railroad maps, 310- Description derived from published bibliography.- Available also through the Library of Congress Web site as a raster image.- VaultMedium1 col. map 30 x 48 cm.Call Number/Physical LocationG3880 1861 .L41 RepositoryLibrary of Congress Geography and Map Division Washington, D.C. 20540-4650 USA Digital Id https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3800.fi000077http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3880.rr003100

-

Staid in Lewisburg until evening. It was a quarterly court and a day of great resort in Lewisburg. Started in the evening and came to Pierce’s [Pierie’s] ten miles over the Muddy Creek Mountain. Fared well.

Written in 1829, this is the journal of William M. Campbell. This is also the story of Archer Alexander, an enslaved man born in Lexington, Virginia, who was taken to Missouri in 1829. There are 38 entries in Campbell’s journal, which begins on August 20, 1829 that you can read and follow the story of Archer Alexander. Campbell’s journal is located in the Archives at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia and is being shared here so that we may hear all the voices, including those whose voices were not shared originally. The photos were taken by me when visiting Virginia for research and then following the pathway that Campbell shares in his journal. Please keep in mind the context of the time in which this journal was written. Feel free to share your comments directly on this blog or join in on the discussion in the St. Charles County History Facebook Group. You may sign up for email alerts of the daily blog posts below.

Lewisburg Courthouse where Campbell spent the day.

-

Came to Callahan’s for breakfast. A fine Tavern stand. Finely kept by the owner who is much a gentleman. We now commenced traveling on the turnpike. The road is very excellent considering the mountainous regions through which it passes – crosses the Alleghany. Passed the White Sulpher Springs where there were two hundred visitors. This is the most valuable mineral water in the world and would be frequented by double the present number of visitors if there were good roads to it and it was owned by an active and energetic man. Crossed Greenbrier River by the finest bridge in Virginia Toll 93-3/4 cents and came to Louisburg in the evening. Met many acquaintances with some of whom we staid.

For the full story see: https://archeralexander.blog/2023/08/23/entry-4-from-virginia-to-missouri/

Written in 1829, this is the journal of William M. Campbell. This is also the story of Archer Alexander, an enslaved man born in Lexington, Virginia, who was taken to Missouri in 1829. There are 38 entries in Campbell’s journal, which begins on August 20, 1829 that you can read and follow the story of Archer Alexander. In Campbell’s journal is located in the Archives at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia and is being shared here so that we may hear all the voices, including those whose voices were not shared originally. The photos were taken by me when visiting Virginia for research and then following the pathway that Campbell shares in his journal. Please keep in mind the context of the time in which this journal was written. Feel free to share your comments directly on this blog or join in on the discussion in the St. Charles County History Facebook Group. You may sign up for email alerts of the daily blog posts below.

[Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https///www.loc.gov/item/2006679024/.jpg -

Made an early start, crossed the Warm Spring Mountain, lately improved by turn piking. Passed the Warm Springs where there were forty visitors and Hot Springs, where there were sixty. Were detained on the road by the oversetting and breaking of a South Carolina Sulky. We met in a narow place and he capsized and we had to help him refit before he could proceed; crossed Jackson’s River and the steep Morris Hill and came to the Shoomates [Shumates] at dark. He was an officious, sensible, kind and talkative landlord. This road is crowded with travelers passing to and from the springs. Our horses came.

PHOTOS BY DORRIS KEEVEN-FRANKE

Written in 1829, this is the journal of William M. Campbell. This is also the story of Archer Alexander, an enslaved man born in Lexington, Virginia, who was taken to Missouri in 1829. There are 38 entries in Campbell’s journal, which begins on August 20, 1829 that you can read and follow the story of Archer Alexander.Campbell’s journal is located in the Archives at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia and is being shared here so that we may hear all the voices, including those whose voices were not shared originally. The photos were taken by myself when visiting Virginia for research, and then following the pathway that Campbell shares in his journal. Please keep in mind the context of the time in which this journal was written. Feel free to share your comments directly on this blog or on Archer Alexander’s Facebook page. You may sign up for alerts of the blog posts below.

-

Took a final leave of all my fathers family and turned our faces toward the West. We found the roads very bad and of course traveled slowly. Crossed the North Mountain and at noon ate a harty meal of bread, beef and cheese at a spring on the side of Mill Mountain. Fed at Williams and started for Warm Springs about 3 o’clock. We had not proceeded more than two hundred yards before we broke a singletree and were detained until almost night to have a new one made. Then drove four miles to Stewards. Fared well on a plenty of plain substantial food.

And so begins the journal of William M. Campbell from Lexington, Virginia to Dardenne Township in St. Charles County Missouri. Begun in August of 1829, the group of over fifty travelers would have twenty-five enslaved individuals, including Archer Alexander, between three families, the Alexanders, McClures, and Wilsons . Enslaved there were six boys under the age of ten, three young males between ten and twenty-three, two young men between twenty-four and thirty-six, and one older man between thirty-six and fifty-four. Also there were four little girls under the age of ten, seven young women of child-bearing age between ten and twenty-three, two older women still of child bearing age between twenty-four and thirty-six, and one older woman also between the age of thirty-six and fifty-four. Among these was Archer’s newborn son Wesley, and his mother, the black nurse for the McClure’s newborn baby Sally McClure.

This journal of a journey from Lexington, in Rockbridge County in Virginia to St. Charles County Missouri was written between August through October, 1829, includes the enslaved Archer Alexander. Written by William M. Campbell (1805-1849) the son of Samuel LeGrand Campbell (1765-1840) , the second President of Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia and his wife Agnes Reid Alexander (1772-1846). It can be found in the Leyburn Library, Special Collections and Archives, located at the Washington and Lee University, in Lexington, Virginia. A very special thanks goes to Lisa S. McCown, Senior Assistant and all of the staff there. . This journal is presented here with the spellings as presented by the writer in 1829. All photos by Dorris Keeven-Franke.

Written in 1829, this is the journal of William M. Campbell. This is also the story of Archer Alexander, an enslaved man born in Lexington, Virginia, who was taken to Missouri in 1829. There are 38 entries in Campbell’s journal, which begins on August 20, 1829 that you can read and follow the story of Archer Alexander.Campbell’s journal is located in the Archives at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia and is being shared here so that we may hear all the voices, including those whose voices were not shared originally. Please keep in mind the context of the time in which this journal was written.

SUBSCRIBE TO STCHARLESCOUNTYHISTORY.ORG FOR FREE DAILY EMAIL WITH STORIES ABOUT ST CHARLES’ HISTORY

FOR MORE ABOUT ARCHER ALEXANDER SEE https://archeralexander.blog/

-

First Entry – The Journey begins 8.20.29

I started from Lexington, Virginia on a journey to the state of Missouri. My own object in going to that remote section of the Union was to seek a place where I might obtain an honest livelihood by the practice of law. I travel in company with four families containing about fifty individuals, white and black. The first family is that of Dr. McCluer, his wife (my sister) and five children from six months to thirteen years old and fourteen negro servants. Two young men, McNutt and Cummings, and myself form a part of the traveling family of Dr. McCluer. Dr. McCluer leaves a lucrative practice and proposes settling himself in St. Charles County Missouri on a fine farm which he has purchased about 36 miles from St. Louis. The second family is that of James H. Alexander, who married a sister of Dr. McCluer, with five children and seven negro slaves. Intends farming in Missouri. Third family, James Wilson, a young man who is to be married this night to a pretty young girl and start off in four days to live one thousand miles from her parents. He has four or five negroes. Fourth family, Jacob Icenhoward, an honest, poor, industrious Dutchman with several children and a very aged father in law whom he is taking at great trouble to Missouri, to keep him from becoming a county charge. He has labored his life time here and made nothing more than a subsistence and has determined to go to a country where the substantial comforts of life are more abundant.

Our caravan when assembled will consist of four wagons, two carryalls, one Barouche and several horses, cows.and fifty people. Two of Dr. McCluer’s children are in Charleston, Kenahwa, with their Uncle Calhoun. Our caravan will not start until the 25th of August. But I, with my sister and nurse will proceed forthwith in the Barouche to Charleston, Kenawha, where we will await the arrival of the caravan. This evening we left Lexington, our native town; possibly never to see it again.

I bid adieu to numerous friends and acquaintances, all of whom professes to wish me well. Many of them sincerely, some of them from the bottom of their hearts, some deceitfully and others with indifference. I parted from many whom I respected and esteem highly. I left a numerous tribe of relatives and many old friends. Many requested me to write to them and give them an account of the country and numbers intimated a hope of coming to Missouri in a few years. We came three miles to the residence of my aged father and mother with whom we stay all night, perhaps for the last time. Tomorrow morning we will start in our barouche for Warm Springs.

More of this story can be found on my blog post https://archeralexander.blog/2021/08/20/from-virginia-to-missouri/

SUBSCRIBE TO STCHARLESCOUNTYHISTORY.ORG AND GET A FREE EMAIL WITH A STORY EVERY DAY IN YOUR INBOX…

-

By the end of the 1820s, St. Charles County’s population had grown to 4,320 white Americans living here, primarily from the states of Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee. They had brought their enslaved with them, amounting to a total of 476 males, and 475 females for a total of 951 African-Americans, approximately 18% of the total population. There were also twenty seven free blacks living in the county. Its 470 Square miles encompassed forests, creeks, rivers, and prairie land. The principal crops were tobacco and hemp, which required large enslaved labor forces. But a huge wave of new settlers were on their way. In the next decade, the population would nearly double. Things were about to change…

On August 20, 1829, a group of three families, the Alexanders, the McCluers, and the Wilsons, would be joined by a large family named Icenhaur, would depart from Rockbridge County, in the Shenandoah Valley. Their cousin William Campbell, would keep a journal of that trek to Missouri, giving accounts of where they stopped, and what kinds of inns and innkeepers they would encounter. In reading this account and following their journey, we learn what such a journey is like for families coming here to St. Charles County. There are over fifty people in this caravan, half of them are white, and half of them are black. One of them, is an enslaved man named Archer Alexander, with his wife Louisa, and a son named Wesley.

-

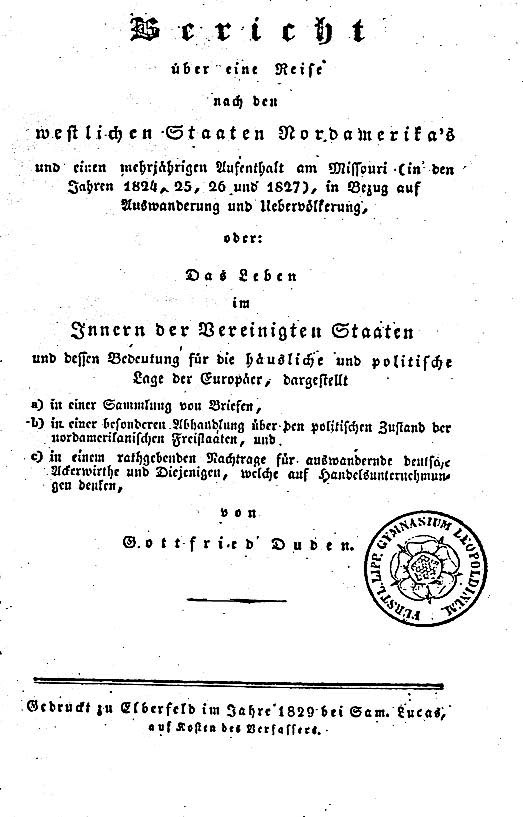

Ever wonder why so many Saint Charles families trace their ancestry back to Germany? Some would say one visitor who arrived in 1824 might just be the reason. He would spend three years here visiting with Nathan Boone, Jacob Zumwalt, and others, observing the life of those who had already uprooted their families and headed west. They had a reason to head to this new territory….

In 1829, Gottfried Duden published at his own expense 1500 copies of a small book titled Report on a Journey to the Western States of North America in Elberfeld Germany. In 1909, eighty years after Duden’s Report was published, A.B. Faust described Duden with, “His skillful pen mingled fact and fiction, interwove experience and imagination, pictured the freedom of the forest and of democratic institutions in contrast with the social restrictions and political embarrassments of Europe. Many thousands of Germans pondered over this book and enthused over its sympathetic glow. Innumerable resolutions were made to cross the ocean and build for the present and succeeding generations happy homes on the far-famed Missouri.”

In 1919, ninety years following Duden’s Report, Duden’s first biographer William G. Bek begins with, “Duden was the first German who gave his countrymen a fairly comprehensive, and reasonably accurate, first-hand account of conditions as they obtained in the eastern part of the new state of Missouri.”

In Mack Walker’s Germany and the Emigration 1816-1885 we find, “Duden’s enthusiastic book . . . fits its time with a gratifying neatness; for it first appeared in 1829, just as the Auswanderung to America was beginning to revive. But it not only met a need and suited an atmosphere it helped appreciably to create them. Duden’s descriptions of American landscapes and American resources were vivid, even lyrical. He found American economic, political, and social conditions better than those of the Fatherland, and American intellectual and moral conditions just as good. The color, timing, and literary qualities of Duden’s report made it unquestionably the most popular and influential description of the United States to appear during the first half of the century. It was an important factor in the enthusiasm for America among educated Germans in the thirties; it served for decades as a point of departure for hundreds of essays, articles, and books, and innumerable thousands of conversations; it was a landmark in the life and memory of many an Auswanderer.”

Nearly one hundred twenty-five years following Duden’s Report, Charles van Ravenswaay in his epic The Arts and Architecture of German Settlements in Missouri: A Survey of a Vanishing Culture tells us, “This timely work . . . greatly stimulated immigration to the United States and caused thousands to make Missouri their destination . . . For more than a generation Duden’s writings formed the leitmotif of German settlement in Missouri, with the interpretation of his comments provoking endless discussion among those who came here. Many immigrants continued to revere his memory as the father of the German migration, and even those who blamed him for their misfortunes seem to have had a grudging respect for that kindly, guileless man.”

Born in 1789 in the small town of Remscheid, Duden was the son of a wealthy apothecary and his second wife. When Duden was six years old his father died, leaving a widow and five children, and Duden the middle child with two older brothers, and two younger sisters. When one of the older brothers died, Duden was only nine, more thought was certainly placed on whether he would follow in the family’s apothecary business. Instead his chosen career became law. And as an impressionable, wealthy and highly educated young man, he would suddenly find himself seated behind the law bench in Dusseldorf, listening to the horrid tales of woe, from a world he was certainly not familiar with. His military service, done without pay, raised his awareness further, about the conditions and the problems his country was facing. His generation’s students at the Universities were pushing to change these problems. Others, such as Frederick Ludwig Jahn, with the Turner movement, spoke out about the need for a need for a united Germany, with strong minds and bodies. With the foresight to see, that if the struggles his fellow countrymen faced, could not be changed, perhaps a fresh start in that young country in North America should be made. Duden was not the first, nor was he the only German author to consider authoring an “emigration book” as hundreds were being published by this time. But did they know what they were talking about? Most authors had never even been there, and those that claimed to, Duden would soon discover really had not. Inspired by the tales of pioneers such as Daniel Boone, Duden began to look closer at the new territories opening in the far west.

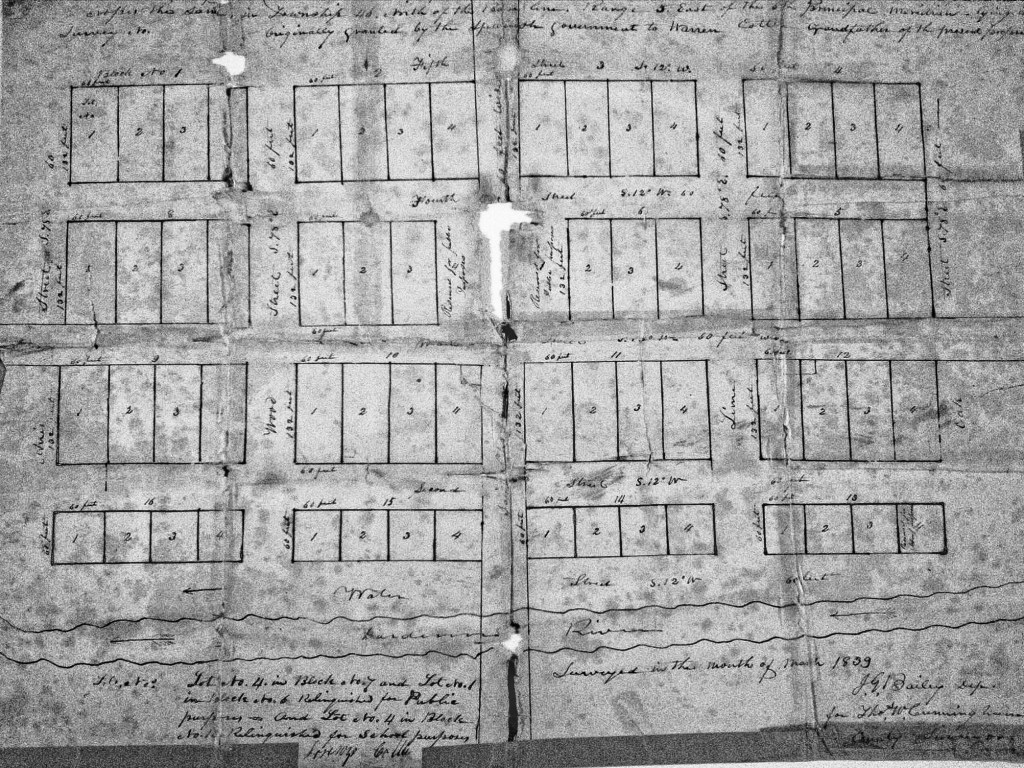

Using an agent, in 1819, Duden purchased property in the U.S. Land Office. It lay near the Fifth Principal Meridian, in what had been Saint Charles County, but was then Montgomery County, and today is Warren County, the village of Dutzow. He developed a plan, which would be thwarted when a chosen companion died in South America. Soon he would have another, Ludwig Eversmann, and he, and his cook Gertrude Obladen, would join him in the young State of Missouri, where he purchased even more land.

For three years, Duden would write about his time in the Western States, compiling notes about everything from his neighbors to the conditions of the U.S. Government. Thorough, he covered the issues of slavery, the American Indians, and farming, from a nearby hillside on Jacob Haun’s farm. Farming, was only by observation, as that was what he had brought Eversmann for. He roamed the countryside and went duck hunting with Nathan Boone. When he readied for his return to Germany, the locals asked why he was going back to conditions he considered so bad, and he stated that Eversmann would stay and take care of his farm, but Duden’s mission was to publish a book. A book in which he would compare, like no other at that time, Germany to North America. He would report, in a matter of fact manner, how a farmer could purchase land, raise a family, and worship freely in the church of his choice. He was free to raise all the crops he wanted on his land, and kill all of the meat his family could eat, that his labor allowed. He was free to marry, cut whatever wood he needed for his house and his fire, and vote to decide on his leaders. He was free. Here one was free to do all of these things, while in Germany most were not. With no military draft, no inheritance laws, and no high taxes, this would sound like a virtual Schlafferenlande – a Garden of Eden.

When Duden’s A Report on a Journey to the Western States of North America hit the bookstores in 1829, it was an instant hit! It literally flew off the bookstores’ shelves, going straight to the top of the bookseller list, and had everybody talking, all without the help of today’s blogs, tweets and Facebook. Included in the back was Duden’s advice to the farmer, and suddenly everybody wanted to be a “farmer”! Soon thousands would leave German ports such as Bremen, and arrive at Baltimore or New Orleans, declaring them self a farmer. For the first decade, Duden’s advice to travel through Baltimore and in groups, for safety, was usually heeded.

First only a small trickle, with the little so called Berlin Society, funded by Baron von Bock, establishing Dutzow, named after his estate in Germany. Soon to be followed by a ships filled with Germans from Osnabruck and then Soligen, hundreds more soon filled the Missouri River valley. Emigration Societies in Germany and Switzerland republished Duden’s book, with second, third and fourth editions soon to follow. Emigration Societies here in the U.S. were formed, in Philadelphia, which purchased land and sold shares, creating Missouri towns like Hermann.

The impetus was on, and when charismatic leaders such as Paul Follen, and Friedrich Muench, with their Giessen Emigration Society, gave a call for a large group to emigrate in mass, the response was huge! Their impossible goal to create a German Republic in the United States as they originally planned may have failed, but the idea of a State where Germany’s cultural heritage could live on, definitely did not. Thousands wanted to be part of Muench and Follenius’ movement, and seek their freedom and fortunes in the New World.

Not only to be restricted to the wealthy, freedom for religious faiths would soon find inspiration in Duden’s book, with leaders like Martin Stephans, who corresponded with Duden. And finally, in the end, not to be restrained by class or religion, entire villages would be emptied, as letters home or chain migration picked up the baton passed on to them. Soon Duden’s book, would be replaced somewhat, by even more personal, first hand accounts written by his followers. These letters, written by relatives to family members still in Germany, and shared after church on Sunday, in the wine garden, or during drills at the Turnverein, kept the waves of emigrants coming. With stories of how they ate more meat in a day or week, than their relatives did in a month. Or, how with a little hard work, they could purchase land, to raise large families. And how best of all, they were free, free to speak their own mind, to be part of the electoral process and to worship where they chose.

While I could go on, and would love to continue, about the achievements of these early emigrants and their bold moves which brought us to today.Gottfried Duden died on October 29, 1856. And while he never returned to Missouri, he did keep his own dream alive, with ownership of his small Missouri farm with the cows on it. Today, one can still purchase books on the subject of emigration, in both Germany and the U.S. and find Gottfried Duden included. Duden’s personal ambition to help his fellow countrymen was fulfilled with his Report. While criticized for his romantic descriptions, immigrants could not deny that “while all things were not exactly as Duden described, in some ways they were even better.” His Report, inspired great leaders, and gave rise to thousands, to chose to emigrate to the land where “the sun of freedom shines” forever. This legacy lives on today, in the hundreds of thousands of immigrants, and their descendants, in the United States.

Today, we can still find evidence of those early emigrants in our architecture, customs and traditions. Our history books cite their roles in the Civil War, and in the industry found in their businesses. We celebrate our holidays with Christmas trees and cookies. We toast our successes with wine. Our love of parties and celebrations, of commemorating each moment, cannot be quashed by blue laws. We educate our children starting with Kindegarten, and teach the importance of schooling, freely, and for all. Today still, our traditions keep the dreams, the culture, and the faith of those first bold moves alive.

SUBSCRIBE AND GET FREE DAILY EMAILS OF STCHARLESCOUNTYHISTORY

-

Edward Bates was born in 1793, in Goochland County, Virginia. In 1814, he would follow his brother Frederick, who had been appointed by President Thomas Jefferson as Secretary of the Louisiana Territory. Edward studied law under Rufus Easton, the Territory’s Chief Clerk, and then serving on the Supreme Court, he would receive his bar degree in 1816. In 1820, he would serve in the State Convention , after being one opposed to the restriction of slavery. In 1822, he would serve Missouri in the House of Representatives, located in the village of St. Charles.

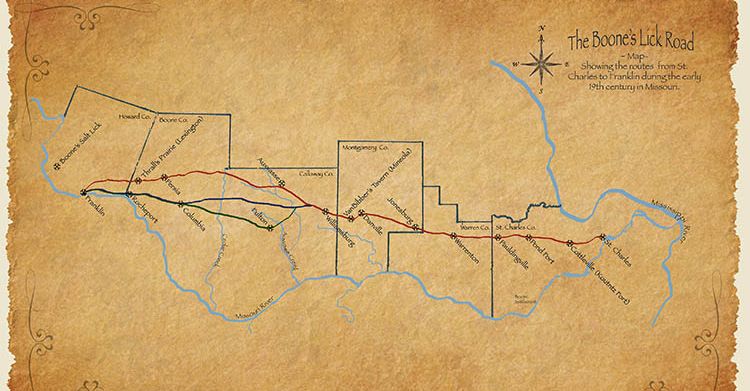

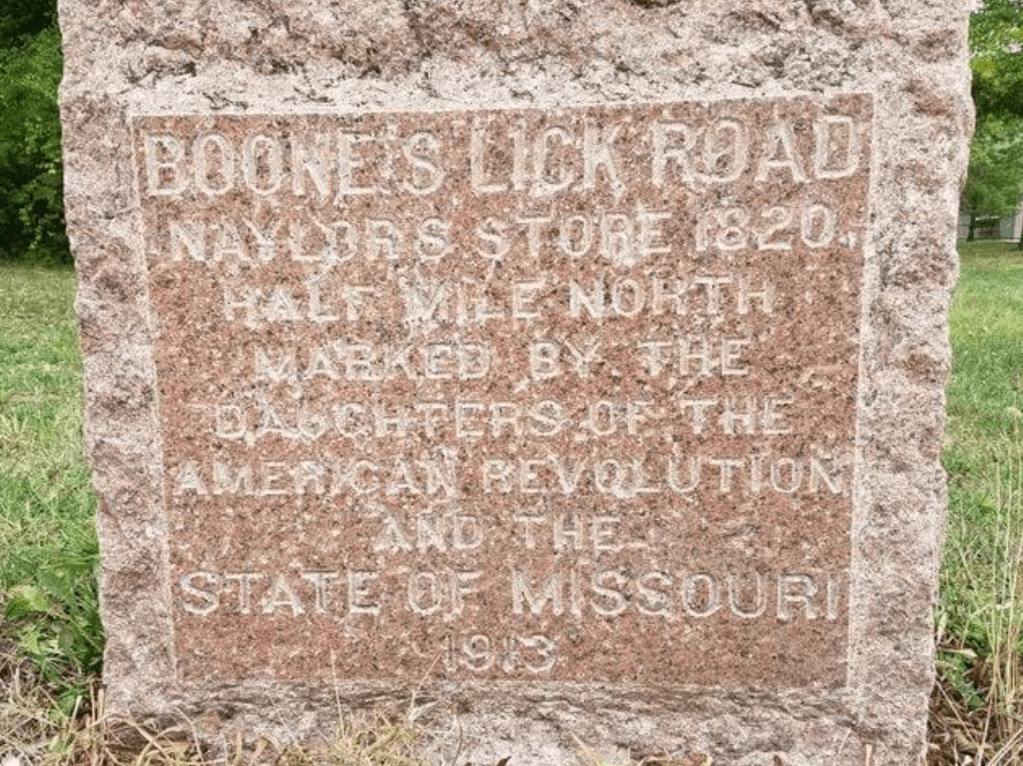

Edward Bates’ brother Fredrick Bates would serve as Missouri’s second Governor, where he would die while he was in office in 1825. The first State Capitol would move from St. Charles to Jefferson City in November of 1826. Edward Bates would establish his home on the Boone’s Lick Road (Today’s Highway N) in Dardenne Prairie in 1829, naming his huge plantation of 500 acres Walnut Grove. There he built a 22-room mansion, the largest in St. Charles County and name it Chenaux. The huge home was flanked by two large twin Chimneys. (The home is no longer standing.)

In 1844, Edward Bates would serve as the pro-bono attorney for Lucy Berry, later known as Lucy Delaney, author of the 1892 slave narrative “From the Darkness cometh the Light”. Her case, which Bates won, served as the inspiration for the freedom suit of Harriet and Dred Scott. “Despite his efforts on behalf of freepersons like Lucy, Bates had reservations against exerting greater pressure on slavery itself. Personally, his actions regarding enslaved people were in line with his contemporaries who exhibited no personal qualms with treating Black people unequally. At times, Bates hired out his enslaved servants to his neighbors. At others, he profited from their sale.” [i]

During the Civil War, Edward Bates would serve in President Abraham Lincoln’s Cabinet as the United States Attorney General from 1861until 1865. When Edward Bates retired and returned to Missouri, his son Joshua Barton Bates was living at the family’s estate in Dardenne Prairie and raising his family. President Lincoln had appointed Barton Bates as a Missouri Supreme Court Judge in 1862.

From the Twin Chimneys Elementary which was built in 1993: Most of the Winghaven Development is located on what was the Bates’ property. Even now, if you superimpose the 1800’s property map over present day satellite images, they are still eerily similar. The part of the Twin Chimneys subdivision, Little Oaks, is where the original residence, Cheneaux stood. In our Twin Chimneys Elementary community, there are still signs of Judge Bates and his family. Many streets in the adjacent subdivision are named after the Bates family. Bates road of course, Onward Way for the Judge’s oldest son, Thornhill was the name of the residence owned by an uncle, and Watson’s Parish was named after the Reverend Thomas Watson of Dardenne Church.

Endnote

[i] Neels, Mark A, Lincoln’s Conservative Advisor, Southern Illinois Press, 2024

SUBSCRIBE AND RECEIVE A FREE DAILY DOSE OF ST. CHARLES COUNTY HISTORY IN YOUR EMAIL

-

News of the Portage des Sioux treaties sent a message to residents of eastern states; it was now safe to emigrate and homestead in the Missouri Territory. From 1816 to 1820 settlers “came like an avalanche” wrote missionary John Mason Peck. “It seemed as though Kentucky and Tennessee were breaking up and moving to the Far West.” The treaties also had political ramifications. Missouri filed for statehood in 1820 and William Clark failed in his election bid to become the new state’s first governor. Voters viewed him as being “too soft” on the Indians at Portage des Sioux. Jefferson’s plan of coercion through commerce had worked, though not exactly as he envisioned it. The treaty of Portage des Sioux reaffirmed the process of depriving the Osage of their land and it opened the door for a flood of settlers who rapidly filled the old Osage domain and clamored for more. At the beginning of 1808 the Osage dominated nearly 1/8th of the Louisiana Territory but in just 17 years, they were left with a reservation only 50 miles wide and 150 miles long in southern Kansas. The Treaty of Portage des Sioux which meant peace to the United States only added to the change and turmoil being experienced by the Osage Nation.

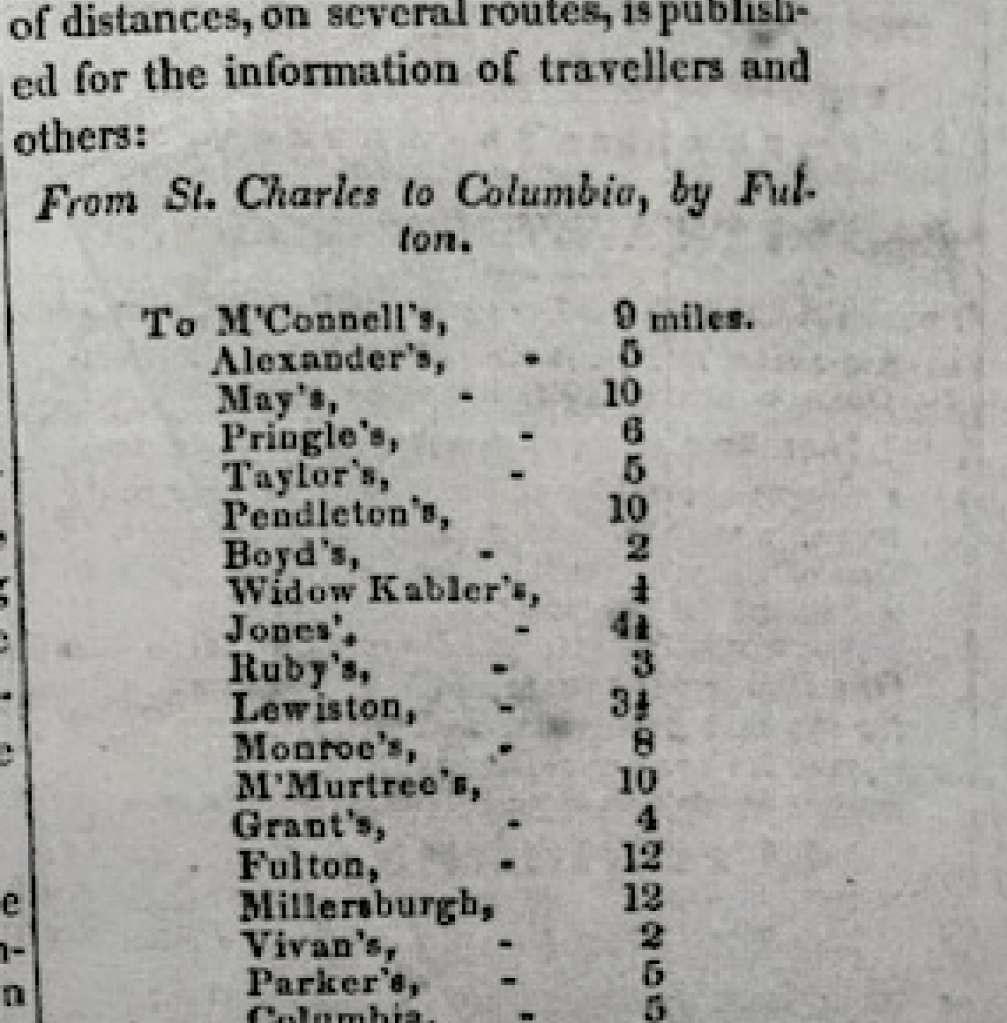

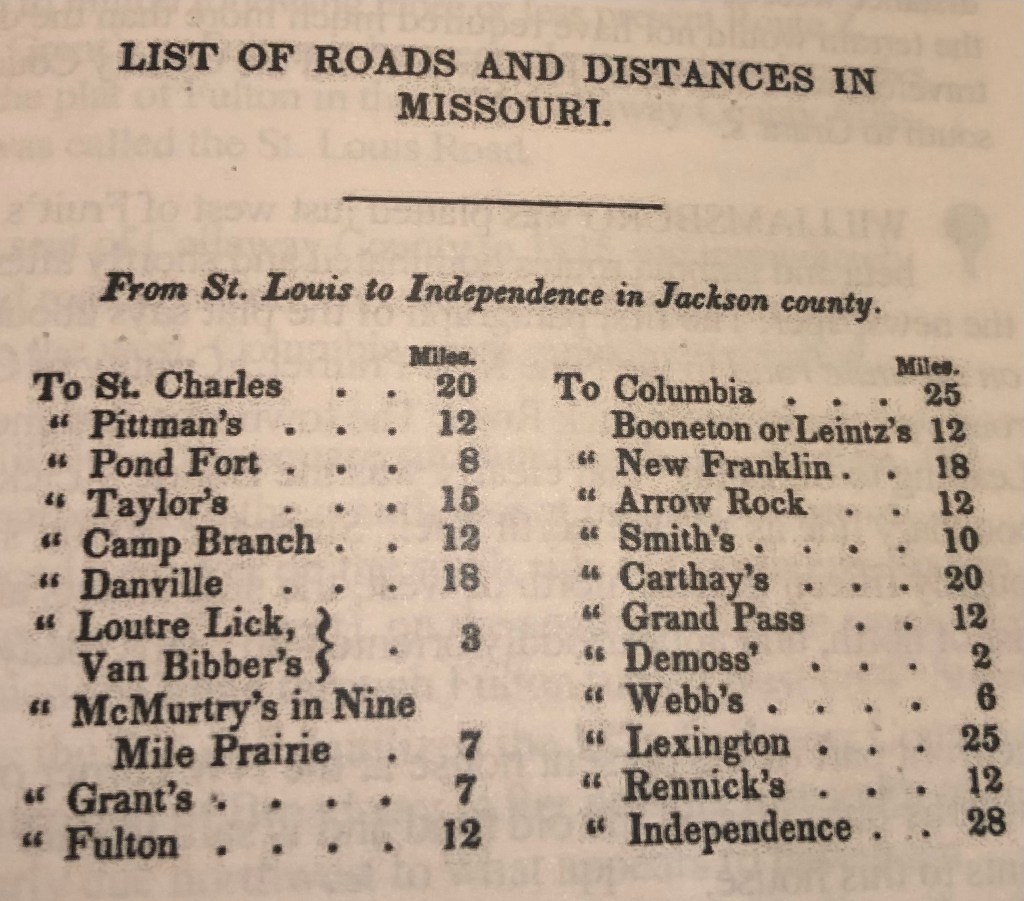

In 1816, John Pitman (1753-1839) and his neighbors would file a Petition, asking the Government to assign a surveyor to lay out a road to the most western edge of U.S. settlement at that time, called the Booneslick. That road would become today’s Boone’s Lick Road. In 1816, roads were named by where they were headed! As this old Buffalo trace, turned into a trail, it was because the population was growing. Veterans of the Revolutionary War, like Pitman, had been awarded Land Grants for their service. Pitman had moved to Missouri by 1816, bringing many of his family and his relatives with him. His brother Thomas Pitman (1750-1825) had settled at Howell’s Prairie, near the Missouri River.

Pitman’s Land Warrant was issued for land in the Arkansas Territory in 1821, but he had already moved his family to Missouri by that time. He sold that land warrant to a relative, using it to enlarge his amount of property here in St. Charles County. But in 1816, he was one of a growing number of St. Charles County residents that realized that the Territory was growing, and that good roads were important. And just like James Morrison on St. Charles’ Main Street, who owned the Bryan and Rose Salt lick at the other end of the Boone’s Lick Road, Pitman wanted to make sure that his land would be on “the big road” as it was often referred to at that time.

In 1818, U.S. Land Sales Offices had opened an begun selling land using the Public Land Survey System of a Section Range and Township, which Thomas Jefferson had encountered in France. When the U.S. purchased the Louisiana Territory from France in 1804, it didn’t come with any records of who owned what land already. Besides sending out the explorers Lewis and Clark, surveyors were needed to lay out these grids. With the War of 1812, that process would be interrupted. After the treaties, work would begin anew by surveyors. However, the U.S Land Office was also involved at the same time, in identifying who already owned what land. Early settlers like Daniel Boone, Warren Cottle and Jacob Zumwalt had already purchased land prior to 1804. These early land grants from the Spanish were called into question and they had to prove to the new government that they truly owned the property. There was also a lot of land speculation and those that tried to claim land that they didn’t actually owned. And there were those who didn’t own land, but had simply “squatted” on a parcel calling it theirs.

This was a difficult time, as we were just a Territory, and with little representation in D.C., and thoughts of Statehood were beginning. The demographics were changing as well, as the fur traders were giving way to those coming from the states of Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee buying up huge swaths of cheap land and bringing their cheap labor force, the enslaved, with them.

Land Warrant for John Pitman for his service in the Revolutionary War. RESOURCES

For More about Missouri’s Land Sales and where to obtain records see the Missouri Secretary of State Archives website:

Follow links within our blogs and they will take you to previous posts that have more information. Or you can use the Search function below to search categories, tags, or previous posts.

-

Written by Michael Dickey – Former Site Director, Arrow Rock State Historic Site, Missouri Department of Natural Resources for the Program: April 25, 2015 Conflicted Perspectives Symposium, St. Charles County College and the Peace and Friendship Commemoration on September 15, 2015.

President James Madison appointed William Clark, Illinois Territorial Governor Ninian Edwards and U.S. Indian Agent Auguste Chouteau as Indian Peace Commissioners and they were convened from May 11 through September 28. They were appropriated $20,000 in trade goods to use as presents for the Indians.[19]

They invited about 19 western tribes (some were actually bands of tribes) to meet and council at Portage des Sioux. This location was convenient to the tribes on the Missouri, upper Mississippi and Illinois Rivers, and it was far enough from St. Louis and St. Charles so as not to impact the daily activity of the citizenry. Fort Belle Fontaine was only a few miles away and its 275 troops were deployed to the treaty grounds. In early July about 2,000 Indians began gathering at the site. Leaders the pro-British faction of the Sac & Fox did not show up. Leaders of a dozen tribes signed the treaty but others such as the Menominee and Winnebago did not until the following year. Even though the Osage had not fought against the United States they were compelled to affirm their loyalty and re-affirm the treaty of 1808. Eleven chiefs of the Big Osage, one Arkansas Osage chief, eleven Little Osage chiefs and one chief of the Missourias attached to the Little Osage signed the peace treaty on September 12, 1815 which followed a short, simple template:

A treaty of peace and friendship, made and concluded between William Clark, Ninian Edwards, and Auguste Chouteau, Commissioners Plenipotentiary of the United States of America…of the one part; and the undersigned King, Chiefs, and Warriors, of the Great and Little Osage Tribes or Nations…of the other part.

THE parties being desirous of re-establishing peace and friendship between the United States and the said tribes or nations, and of being placed in all things, and in every respect, on the same footing upon which they stood before the war, have agreed to the following articles:

ARTICLE 1. Every injury, or act of hostility, by one or either of the contracting parties against the other, shall be mutually forgiven and forgot.

ARTICLE 2. There shall be perpetual peace and friendship between all the citizens of the United States of America and all the individuals composing the said Osage tribes or nations.

ARTICLE 3. The contracting parties, in the sincerity of mutual friendship recognize, re-establish, and confirm, all and every treaty, contract, and agreement, heretofore concluded between the United States and the said Osage tribes or nations.[20]

At first glance, the wording of the treaty seems harmless enough. No land cessions were required and annuities were not withheld as punishment for any damages attributed to individual Osages during the war. However, the Osages did not regain “the same footing upon which they stood before the war.” Fort Osage reopened that fall, but they did not relocate there. The war had changed the climate of the nation. News of the Portage des Sioux treaties sent a message to residents of eastern states; it was now safe to emigrate and homestead in the Missouri Territory. From 1816 to 1820 settlers “came like an avalanche” wrote missionary John Mason Peck. “It seemed as though Kentucky and Tennessee were breaking up and moving to the Far West.”[21] The treaties also had political ramifications. Missouri filed for statehood in 1820 and William Clark failed in his election bid to become the new state’s first governor. Voters viewed him as being “too soft” on the Indians at Portage des Sioux.[22] Missourians it seems, were not willing to “forgive and forget” as the treaty had stipulated. The Shawnee, Delaware, Kickapoo, Peoria and Cherokees were assigned to reservations abutting the Osage boundary and they frequently hunted on the Osage side of the line. Pressured by the growing settlements of whites and dispossessed eastern tribes, some Big and Little Osage as early as 1808 began joining their Arkansas kinsmen or relocating to southeast Kansas. After 1815 the departures accelerated. The last group of Big Osage remaining in Missouri abandoned their village in the summer of 1822.[23] On June 2 of 1825, the Osage signed a treaty at St. Louis, by which they ceded the remainder of their territory in Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma and much of Kansas[24]

Jefferson’s plan of coercion through commerce had worked, though not exactly as he envisioned it. The treaty of Portage des Sioux reaffirmed the process of depriving the Osage of their land and it opened the door for a flood of settlers who rapidly filled the old Osage domain and clamored for more. At the beginning of 1808 the Osage dominated nearly 1/8th of the Louisiana Territory but in just 17 years, they were left with a reservation only 50 miles wide and 150 miles long in southern Kansas. The Treaty of Portage des Sioux which meant peace to the United States only added to the change and turmoil being experienced by the Osage Nation.

Endnotes

[19] March, David. The History of Missouri Vol. I. Lewis Historical Publishing Co. New York 1967, p. 303

[20] Kappler, Charles J. Indian Affairs Laws and Treaties Vol. II Washington, Government Printing Office, 1904. Treaty With the Osage 1815 http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/Vol2/treaties/osa0119.htm

[21] Babcock, Rufus, ed. Forty Years of Pioneer Life Memoir of John Mason Peck D.D. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1965 p. 146

[22] March, p. 305

[23] Burns, p. 50

[24] Kappler, Treaty With the Osage 1825 http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/Vol2/treaties/osa0217.htm

On September 15, 2015, the Commemoration of the Peace and Friendship Treaties took place at the same location as the original signing, Portage des Sioux in St. Charles County. Present were St Charles County Executive Steve Ehlmann, Osage Nation’s Chief Standing Bear, and William Clark’s descendant Bud Clark.

Drum of the Osage Nation

September 15, 2015

Dorris Keeven-Franke, Bud Clark, Chief Standing Bear

L-R Steve Ehlmann, Chief Standing Bear, Dorris Keeven-Franke By Dorris Keeven-Franke

-

By Michael Dickey – Former Site Director, Arrow Rock State Historic Site, Missouri Department of Natural Resources for a Program: April 25, 2015 Conflicted Perspectives Symposium, St. Charles County College

The War Department in 1808 instituted the factory system to implement Jefferson’s vision. Factories were government fur trading posts that competed directly with private traders in an effort to pacify and control Indians. A military garrison was assigned to protect each factory. Meriwether Lewis proposed that the factory for the Osage be located on the Missouri River as travel on the Osage River was often limited due to low water conditions.[9] In August of 1808 a keelboat under the command of Captain Eli B. Clemson of the 1st U.S. Infantry set out up the Missouri River from Fort Belle Fontaine near St. Louis, followed a short time later by William Clark and Nathan Boone’s overland march of mounted dragoons from St. Charles.[10] The troops rendezvoused at the “Fire Prairie” several miles east of present–day Independence Missouri. There they began construction of Fort Osage, sometimes identified as Fort Clark.

Clark sent Boone and an interpreter out to bring the Osages in to council. Clark employed a carrot-and-stick strategy, threatening war on the Osage but promising that all would be forgiven and they would have their own very trading post if they became American friends. Clark also promised them protection from their enemies.

What pleased most was the idea I suggested that it was better that they should be on the lands of the U.S. where they Could Hunt without the fear of other Indians attacking…than being in continual dread of all the eastern Tribes whom they knew wished to destroy them & possess their Country.[11]

The Osage accepted Clark’s proposal and signed a treaty on September 14. Clark informed Secretary of War Henry Dearborn of the price they paid and what they got in return:

near 50,000 Square Miles of excellent Country – for which I have promised the Osage protection under the guns of the Fort at Fire prairie, to keep a Store at that place to trade with them, to furnish them with a Blacksmith, a Mill, Plows, to build them two houses of logs and to pay for the Horses and property they have taken from the Citizens of the U. States.” [12]

Later a group of 75 Osages arrived in St. Louis returning some stolen horses. They said the treaty was invalid because they had not been present at the signing. They also said that White Hair was a “government chief” who had no authority to make binding agreements for the tribe. Thus, the treaty of 1808 exacerbated existing political dissension in the tribe. The Osages had dealt with the French, British and Spanish for over 100 years on their own terms, sometimes playing them against each other to their own advantage. The French were gone, the Spanish in New Mexico had nothing to trade and the British were too distant to easily trade with. So the Osage could really only deal with the United States and were not able to do so from a position of political unity.

Governor Lewis revised the treaty and Pierre Chouteau was dispatched to Fort Osage to persuade the Osages to sign it. Most of the Big and Little Osage had relocated to the fort. Chouteau had to distribute more gifts and promise an early dispersal of the annuity payments to get them to sign. In the original treaty, a line was drawn straight south from Fort Osage to the Arkansas River and everything east of that boundary to the Mississippi River was ceded. The revised treaty required that they cede an additional 20 million acres of land north of the Missouri River, territory that was also claimed by the Ioway and Sac & Fox nations. However, the government did not consult with those nations about the cession.

The Big Osage became displeased with their new residence and returned to their old towns on the Osage River in 1810. In 1811, war clouds gathered on the frontier as the Shawnee chief Tecumseh built a confederacy of Indian tribes and the British were perceived as inciting the Indians to make war on the United States. The Osage refused Tecumseh’s overtures to join as many tribes in the confederacy were their hereditary enemies. Plus, they weren’t willing to jeopardize the trade at Fort Osage. The British however were reaching out to western tribes to trade in an effort solidify Indian unity. The Osage as U.S. clients and the Ioway as British clients became engaged in a proxy war, receiving tacit support from their sponsors in their raids against each other. After the United States declared war on Great Britain on June 18, 1812, the Little Osage chiefs promised George C. Sibley the fort’s factor (trader), “never to desert their American father as long as he was faithful to them.”[13]

In May of 1813 Frederick Bates, acting Governor of Missouri Territory sought volunteers to defend the Missouri frontier from the pro-British Sac and Fox nation on the Rock River of Illinois. Pierre Chouteau secured 275 first-line Osage warriors for the task. When Governor Benjamin Howard returned from Kentucky he canceled the planned attack, which angered Chouteau and the Osages. Howard and territorial delegate Edward Hempstead distrusted and feared any group of armed Indians roaming the countryside, even though they were allies. Hempstead feared the Osage would change sides at the first opportunity and attack the Missouri settlements. [14]

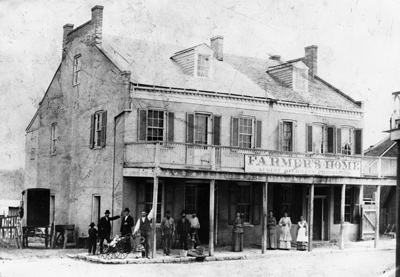

Fort Osage was closed in June of 1813 as being useless to the defense of the frontier. The U.S. still needed to maintain Osage loyalty so Sibley relocated the factory to the Arrow Rock bluff that October. Gray Bird of the Big Osage liked the Arrow Rock location “on account of the Settlements of Americans near it which I think afford us more security when we come to trade.”[15] Gray Bird obviously saw the Boonslick settlement as a buffer between them and their enemies, the Sac & Fox, Potawatomi and Ioway. However, Big Soldier of the Little Osage disagreed with the move:

I was lately on a visit to the Great American Chief. He told me that Ft. Clark should be made stronger than ever, that he would plant an iron post there that could not be pulled up and that would never decay. I fear he has forgotten that promise and instead of planting an iron post intends to let the old wooden one rot. The Trading House is not for nothing. We have given our Sons for it and I tell you plainly I think the President has done very wrong to remove it at all…[16]

The Osage leaders clearly had a higher degree of sophistication and understanding of events going on around them than they are usually given credit for. However dependence on American trade and political disunity in the tribe made it ever more difficult for them to control those events. Despite the Little Osage objections, trade continued at Arrow Rock until April of 1814 when the post was abandoned due to troubling events. Sac & Fox raids in the Missouri valley began increasing. Osage leaders met in council with a faction of the Sac & Fox who been relocated to the Missouri River by Clark the previous September. A Sac chief named Quashquame raised a British Union Jack over the council house, alarming factor John Johnson. [17] Osages robbed trappers on the Gasconade River and killed some hunters on the White River. Some Little Osages traveled to Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin the base of British operations in the Mississippi valley where they received presents. Despite these incidents, the Osage nation did not commit to the British side although Clark on August 14 reported that the British were “making great exertions to gain over the Osages…”[18] Sibley’s operation at Arrow Rock had helped maintain Osage loyalty at a critical juncture as did the influence of Auguste and Pierre Chouteau, who were married into the Big Osage tribe.

Great Britain and the United States signed a peace accord on December 24, 1814 in Ghent, Belgium. Congress ratified the treaty on February 28, 1815 officially ending the War of 1812. However, no provisions were made for the Indian nations involved and peace had to be negotiated separately with each tribe. President James Madison appointed William Clark, Illinois Territorial Governor Ninian Edwards and U.S. Indian Agent Auguste Chouteau as Indian Peace Commissioners and they were convened from May 11 through September 28. They were appropriated $20,000 in trade goods to use as presents for the Indians.[19]

George Sibley 1782-1863 Endnotes

[9] Clarence E. Carter, Ed., The Territorial Papers of the United States, vol. 14, Louisiana and Missouri Territory 1806-1814 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1934-1962) p. 196

[10] Ibid p. 209-210

[11] Clark to Dearborn Sept. 23, 1808 Indian Claims Commission 733 Docket No. 105 The Osage Nation of Indians, 1962 p. 858 http://digital.library.okstate.edu/icc/v11/iccv11bp812.pdf

[12] Carter, p. 225

[13] James, Edwin. An Account of an Expedition to the Rocky Mountains in the Years 1819 and 1820. H.C. Cary, Philadelphia, Vol II 1823, p. 248

[14] Carter, p. 673-676

[15] Ibid p. 714

[16] Ibid p. 714

[17] Gregg, Kate. War of 1812 on the Missouri Frontier. Missouri Historical Review, Vol. 32: 122 – 123

[18] Carter, p. 787

[19] March, David. The History of Missouri Vol. I. Lewis Historical Publishing Co. New York 1967, p. 303

-

By Michael Dickey – Former Site Director, Arrow Rock State Historic Site, Missouri Department of Natural Resources from a Program: April 25, 2015 Conflicted Perspectives Symposium, St. Charles County College

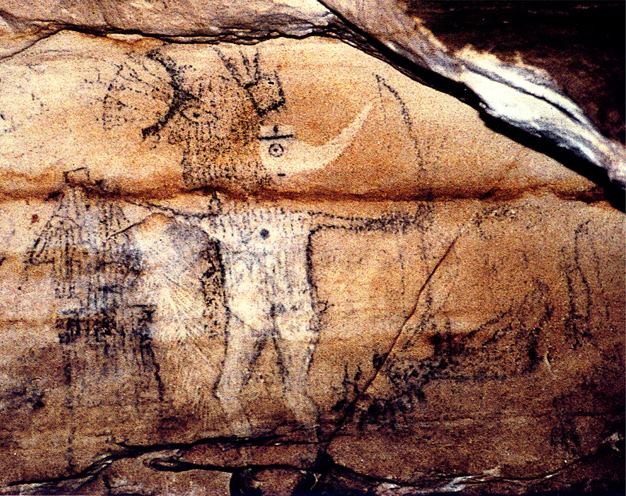

In 1803, the 6,000 strong Osage Nation was the largest, most powerful Native American nation immediately west of the Mississippi River. Adding to that image of power, Osage men averaged over six feet in height, some even reaching seven feet, such as Chief Black Dog painted by western artist George Catlin in 1834. In contrast, the average height of a white American male was only 5 ft. 8 in., strengthening “the idea of their being giants.”[1] The Osage were divided into three bands; the Big Osage on the Osage River, the Little Osage on the Missouri River until about 1795 but now on the Osage River, and the Arkansas Osage on the Verdigris River in northeast Oklahoma. The Osage dominated the region from northern Missouri to the Red River and from the Mississippi valley to the western plains of Kansas and Oklahoma: about 1/8 of the Louisiana Territory.[2]

They aggressively defended their territory against all intruders, Indian and white alike. The Osage could bring all of their 1,250 veteran warriors to bear on a single target in a “grand war movement” a feat that few Indian nations in North America could accomplish.[3] In contrast, the United States had only about 250 soldiers available on the western frontier. Following a meeting with Osage leaders in 1805 President Thomas Jefferson wrote, “…in their quarter, we are miserably weak.”[4] The Osage delegation also visited Boston early in 1806 where Chief Tatschaga delivered a testimonial before the Massachusetts State Senate on how the Osage saw themselves in relation to the United States: “Our complexions differ from yours, but our hearts are the same color, and you ought to love us for we are the original and true Americans.“[5]

By 1808, the Osage became restive as displaced eastern tribes and whites increasingly encroached on their territory. Pawhuska or White Hair the so-called “principal chief” or “grand chief” of the Big Osage was pro-American. The position of the chiefs (actually called headmen) was hereditary; if they lived up to the task for a bad chief could be deposed simply by his people ignoring him. But the real political and spiritual power of the tribe lay with the Non-hon-zhin ga or Little Old Men, a select group of elders imbued with sacred knowledge and tribal history. Chiefs followed the leading and advice of the Little Old Men. European traders and officials interfered with this traditional tribal government by giving gifts and medals to individuals they believed would influence the tribe on their behalf. Pawhuska was not a hereditary chief. St. Louis fur traders Pierre and Auguste Chouteau as representatives of the Spanish government had awarded him medals around 1795. This may have helped further a political schism that was already causing some Big Osage to break away and form the Arkansas Band. [6]

Dissidents to Pawhuska’s leadership harassed American settlers by stealing their horses and killing their cattle. Meriwether Lewis, now the Governor of Louisiana Territory ordered the cessation of all trade with the Osages and invited the Shawnee, Delaware, Kickapoo, Ioway and Miami and Potawatomi to wage war on them.[7] Those tribes did not require much goading because they desired to possess the Osage country which was still rich in wild game, while the wildlife resources in their own territories were rapidly becoming depleted.

Jefferson wrote Lewis that military force should be a last resort, so the attack was called off. “Commerce is the great engine by which we are to coerce them & not war”[8] he told Lewis. Jefferson’s strategy was to create Osage dependence on American commercial trade, thereby creating indebtedness within tribes that they would pay off by ceding land. Reducing their hunting territory in this manner, he believed, would force them to become farmers out of necessity and they would be gradually assimilated into American agrarian society a process taking 50 or more years. He was encouraged by the progress he saw then occurring with southeastern tribes such as the Lower Creeks and Cherokees. But Jefferson failed to understand just how rapidly the frontier would advance and how resistant to cultural change the Osage would be. Furthermore, Missouri frontiersmen did not share Jefferson’s ideals about assimilating the Osages into American society.

Endnotes

- [1] Bradbury, John. Travels in the Interior of America in the Years 1809, 1810, and 1811. London: Sherwood, Neely and Jones, 1819 p. 11

- [2] Burns, Louis A History of the Osage People University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa AL 2004, pp. 27-37

- [3] Osage elder Jim Red Corn cited in “The Osages at Home in the Center of the Earth – Wa sha she U ke Hun ka U kon scah” an exhibit held in conjunction with Osage Tribal Museum at Arrow Rock State Historic Site, 2004-2005.

- [4] Ambrose, Stephen. Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West Simon and Schuster, 1996, p. 342

- [5] The Smithsonian Journal of History, John C. Ewers, Chiefs of the Missouri and Mississippi Vol. I, 1966 p. 22

- [6] Burns, pp. 129-131

- [7] Lewis to Dearborn July 1, 1808 Indian Claims Commission 733 Docket No. 105 The Osage Nation of Indians, 1962 p. 858 http://digital.library.okstate.edu/icc/v11/iccv11bp812.pdf

- [8] Jefferson to Lewis August 21, 1808. The Writings of Thomas Jefferson. Published by the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association Washington, D.C. 1904 p. 142

From the Gilchrist Museum: Title(s): Chief White Hair, Pawhuska, Oklahoma, Creator(s): Unidentified (Author),Culture: Native American, Osage,Date: 1850 – 1900,Classification: Photographs, Object Type: Photographic Print, Accession No: 4326.4129, Previous Number(s): 72949, Department: , Archive Collection: , Oklahoma Native American Photographs Collection.

-

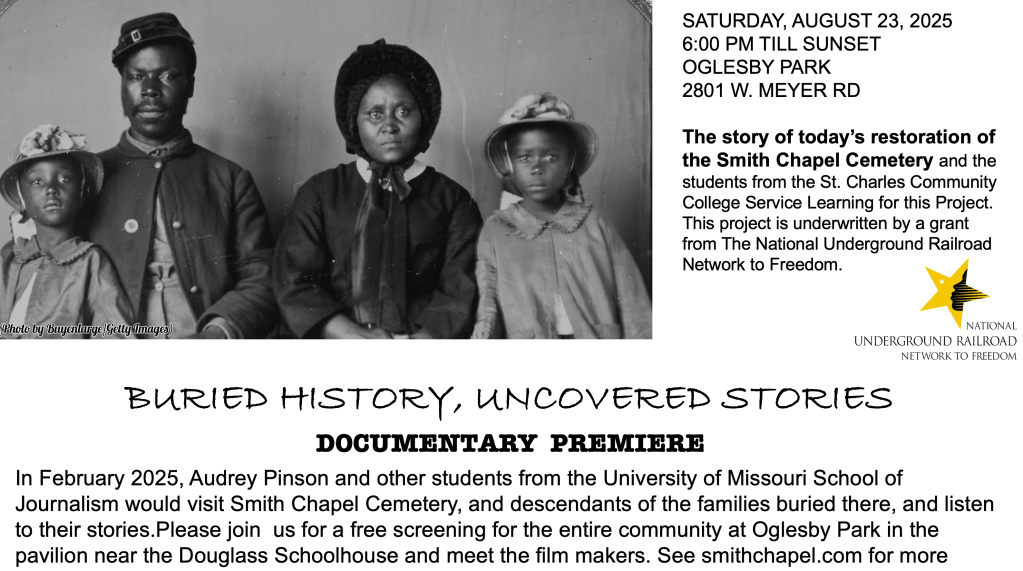

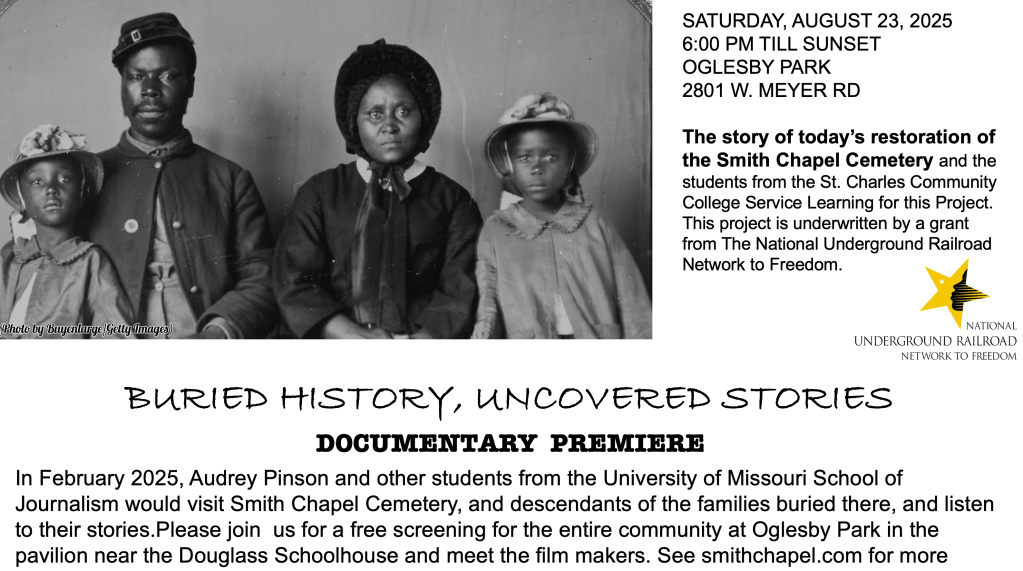

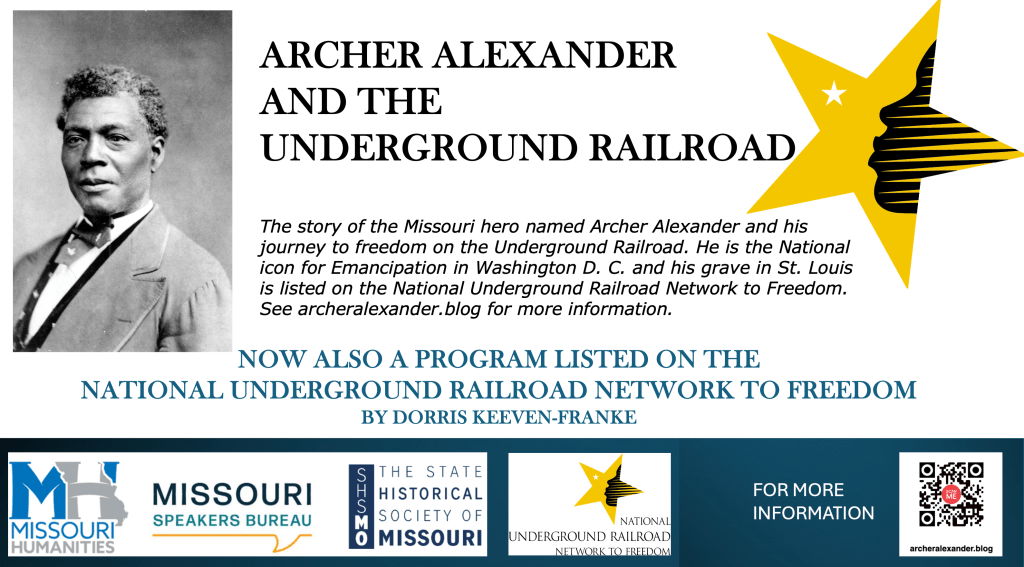

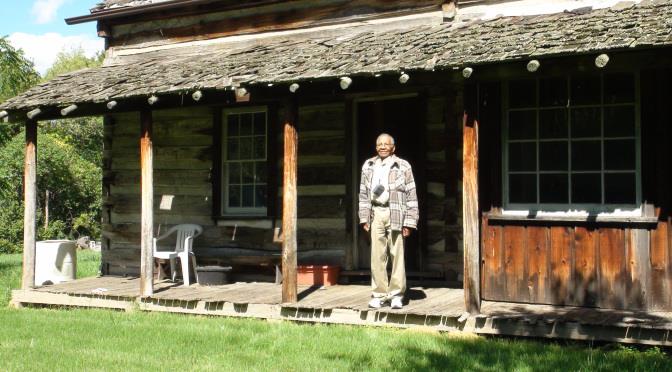

The Smith Chapel Cemetery in Foristell, Missouri is listed on the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom. It is one of over 800 sites across this country that document stories like theirs. The program is a catalyst for innovation, partnerships, and scholarship connecting the legacy of the Underground Railroad across boundaries and generations. The program consists of sites, programs, and facilities with a verifiable connection to the Underground Railroad. There are currently Network to Freedom locations in 40 states, plus Washington D.C., the U.S. Virgin Islands and Canada.

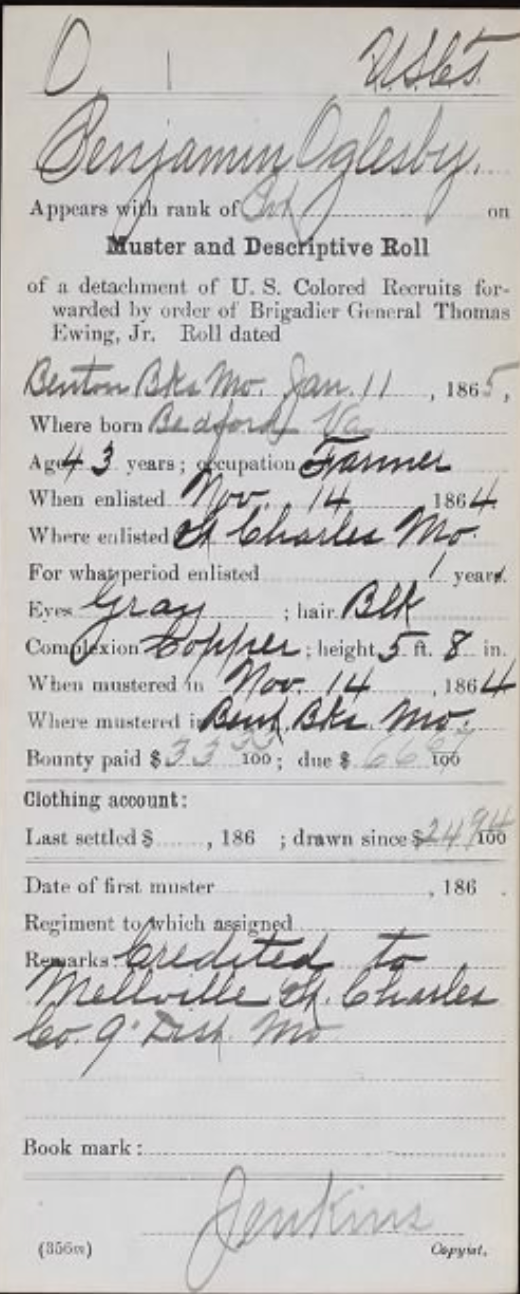

Established in 1871, Smith Chapel Cemetery is an African American burying ground established by nine formerly enslaved individuals in St. Charles County Missouri. At least three men were freedom seekers, and members of the Smith Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church associated with this graveyard. The cemetery is final resting place for Smith Ball (1833-1912), Benjamin Oglesby (1825-1901), and Martin Boyd (1826-1912) who each took steps toward freedom and joined the United States Colored Troops, despite the risks involved for themselves and their families. Living in a border state, these families were caught between the conflict of both Union Troops and Confederate guerilla soldiers. Under Martial law, many Missourians strongly opposed the formation of Colored Troops, only allowing those enslaved to serve as substitutes in their place and to fill County quotas. These freedom seekers, like many others, escaped slavery by the underground railroad, enlisting without permission. Slave Patrols, who kept constant watch of the roads for those attempting freedom, would either return those seeking their freedom to their former enslaver or enforce methods of punishment, which could include death. After the war, these men returned to their families to join others in creating this community.

For 2025, the Smith Chapel Cemetery was awarded a grant by the Network to Freedom to hire a professional cemetery preservationist, Jerry Prouhet, to restore the headstones in the cemetery. It also gave funds for four informational signs to be placed in the cemetery, one at the front that identifies the property, one at the site of the Douglass Schoolhouse (now recreated in Oglesby Park) and one at the Cemetery that will list all of the names of the people buried in the cemetery. The grant also includes for the students at the St. Charles Community College, taking American History 101 Service Learning to actively get involved with the research for the signs, restoring the cemetery, recording Oral Histories, working with their Professor Grace Wade Moser and historian Dorris Keeven-Franke.

In February of 2025, Audrey Pinson and other students from the University of Missouri Columbia – School of Journalism, contacted those working on this project and began work on a documentary about the Smith Chapel Cemetery. The public is invited to the Premiere showing of this documentary on August 23, 2025 at 6:00pm where the film makers, members of the project, descendants of those buried at the cemetery, and students will be available to talk about this wonderful project. Everyone is invited, open to the public, please bring a lawnchair!

FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE SMITH CHAPEL CEMETERY SEE ITS WEBSITE SMITHCHAPELCEMETERY.COM

-

Here on the frontier in 1815, Daniel Boone’s grandson James Callaway (1783-1815), had taken command of Nathan Boone’s company of Rangers at Fort Clemson on Loutre Island (Located at today’s southwestern Warren County border across from Hermann, MO). They were about to mount another campaign, so Callaway had sent many of his men home to prepare, when the alarm came that Sauk and Fox had stolen several horses. Callaway gathered his men still at the Fort and took out in pursuit westward. They followed their trail up the dry fork of the Loutre, and discovered an abandoned Indian camp, with just their horses and a few Indian women there. They retrieved their horses, and turned towards home, with some believing that to return the same way would take them into a trap. It did. As they forded a creek, they were fired upon and Capt. James Callaway was shot. He and five other lives were lost that day.

In May of 1815, atrocities against the settlers continued, despite the events in the East. One of the worst happened when a band attacked the Ramsey family (near Marthasville, Warren County), murdering and scalping the entire family, except a two year old and an infant. The final battle here came on May 24, 1815 with the Battle of the Sinkhole, when Black Hawk and a band of Sauk attacked Fort Howard.(near Old Monroe, in Lincoln County MO) north of the Cuivre River. An ambush on a group of Rangers led to a prolonged siege in which seven of our Rangers were killed.

Finally, word reached the frontier about the end of the war that had happened five months before. President James Madison called for a Treaty to be made with the Indians, and selected Portage des Sioux for the location on September 15, 1815. He appointed Gov. Wm Clark, Illinois Gov. Ninian Edwards, and Col. Auguste Choteau to handle the affair. With the U.S. showing their strength with Col. John Miller and his Third Infantry, and almost the entire force under Gen. Daniel Bissell stationed at Ft. Bellefontaine in place, the drums began to roll. The tribes began arriving July 1st and negotiations lasted for months, with Black Hawk never signing. But the War of 1812, our Indian War, was finally over.

-

War was official on June 18, 1812, and some would call it the “Second American Revolution,” here it would simply be our “The Indian War.” Callaway’s Rangers included settlers from Howell’s Prairie, Pond Fort, Femme Osage and the Boone Settlement. Companies were raised by James Musick at Black Walnut, Robert Spencer at Dardenne, John Weldon of Dardenne Prairie, Benjamin Howell out on Howell’s Prairie, and Christopher Clark in Troy.

Governor Howard, advised those settlers with Benjamin Cooper out near Boone’s Lick, to move in closer to the main settlements where they could be afforded some “smallest measure of protection.” Col. Cooper replied:

“We have made our homes here and all we have is here, and it would ruin us to leave now. We be all good Americans, not a Tory or one of his pups among us, and we have 200 men and boys that will fight to the last and have 100 women and girls that will take their places with [them]. Makes a good force. So we can defend the settlement. With God’s help we do so.” And so they did.

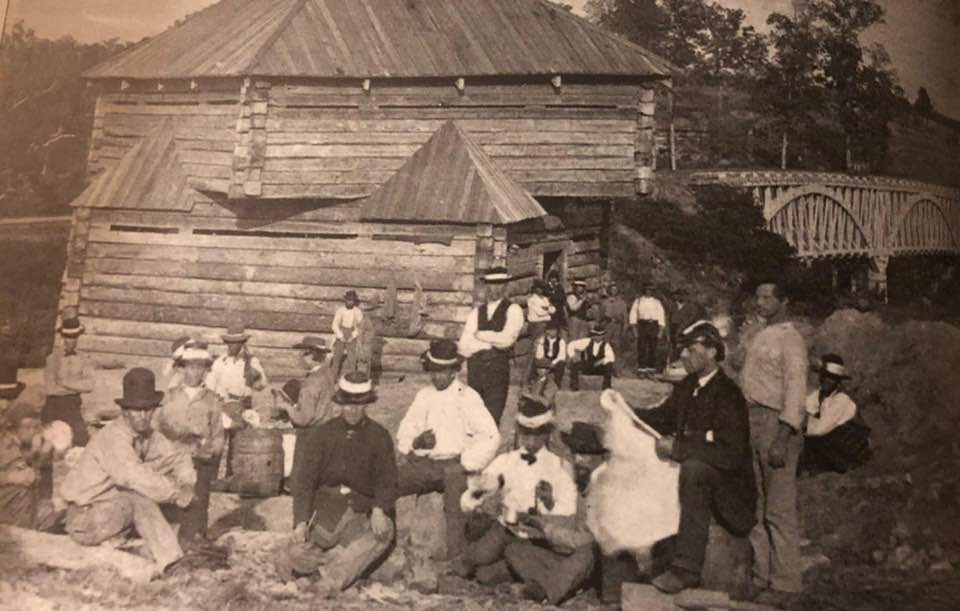

Closer to St. Charles the settlers gathered at Griffith’s farm, Johnson’s farm, Portage des Sioux, Royal Domaine, Wood’s Fort, Clark’s, the Peruque settlement, Price’s farmstead, Baldridge’s farmstead, Zumwalt’s Fort, Kountz’s Fort, and waited. Where ever they could, settlers created forts out of their homesteads or erected house forts. Where there were several families, cabins were erected and stockades connected them, with wells dug, protecting their livestock as well.

Further west on the frontier was Journey’s near Warrenton, Kennedy’s near Wright City, Quick’s Fort and Talbott’s Fort were near McKittrick (now Warren County) and Isaac Best’s and McDermott’s were near Big Spring, and Jacob Groom’s near Readsville (today’s Montgomery County) . North, in today’s Lincoln County, was Buffalo Fort near Louisiana, Stout’s Fort near Auburn, Clarksville had a stockade, Fort Independence, and Fort Mason was near today’s Hannibal.

In August, Winnebagos, Ioways, and Ottos joined nearly 100 Sauk Indians with the British above Fort Mason, and stole horses. A company of Rangers and Cavalry commanded by Capt. Alexander McNair were at Fort Mason at the time. With troops commanded by Col. Nathan Boone,together they pursued the thieves that had made their way to an island on the Mississippi near Portage des Sioux, and were about 200 yards out. When Boone and McNair caught up with them, they fled to the Island’s interior. The troop’s horses were too fatigued to swim, but McNair and his Rangers swam over and recaptured the stolen horses, after they had marched 60 miles that day.

In September, 100 Sioux attacked a settler and his wife, stole their horses and cow, which they slaughtered. Captains Musick and Price pursued the attackers in their canoes. There were said to be at least 70 of them. They recaptured the stolen beef. Then in October, the Van Burkleo family was attacked near Black Walnut. A member of the Militia, Van Burkleo would later serve as an interpreter at the Treaty at Portage des Sioux when the War ended.

Those years were filled with danger, and the settlers were constantly being attacked. Men were torn between serving in the Militia and protecting their families. Pleas were made to the Federal government, who the settlers did not believe were doing enough to protect them. Its location made Saint Charles a passageway for all the Indian nations to the north, who had hunted this area for years prior to the arrival of the white man. Settlement was so scattered that communications were difficult. Just as we were the last to know of the beginning of the War, news of the Treaty ending it, at Ghent on Dec. 24, 1814, was just as slow. Too slow, to prevent the horrible incidents that occurred next.

-

Settlement was sparse, and in clusters. Attacks by the Sauk, Fox, Potowatomis and Iowa increased. They stole horses from the settlers and murdered four members of Stephen Cole’s party when they set out to retrieve them. St. Charles was incorporated in 1809, and by1810 the population of the Territory would reach 20,845 with just over 3,500 residing in our District.