Category: Places

For more about the Boone’s Lick Road visit https://booneslickroad.org/ the Associations Research Library page is full of interesting stories about the places along the road.

When Americans declared themselves independent of Great Britain in 1776, there were three settlements west of the Mississippi, Ste. Genevieve, Saint Louis, and San Carlos. In 1763, Saint Louis had been established on the south side of the great Missouri River, creating what would later become the “Gateway to the West”. Shortly afterwards, in 1769, a French-Canadian fur trader named Louis Blanchette, would establish himself in what was then called “Les Petite Cotes” or the little hills. These hills were the mounds created by the indigenous people that had been living here, for centuries. Travel between St. Louis and San Carlos, followed one of either two pathways, by river or overland. When traveling westward overland, pathways became established, that were ones of the least resistance, which the buffalo and other animals had already discovered. The earliest people, such as the Osage, would follow these same pathways, and establish would be called a “trace”.

As the population increased, so did the use of these early pathways. The first residents were fur traders, who knew that they were leaving the protection of United States but chose to live among the indigenous nations of Osage, Pottawatomie, Sioux and Fox. The land itself though had remained under the flags of the French and the Spanish, being traded first in 1769, and then again in 1799. That year, the well-known trailblazer Daniel Boone, would settle along the Missouri River, south of San Carlos, otherwise known as Saint Charles. Many of those who followed him, were from Kentucky, a State carved from Virginia in the 1770s. These large families brought with them, an enslaved population, that lived under rules known as the Code Noir, or Black Code. All the while, the indigenous population was growing as well, as many were being pushed westward, because of settlement in the Ohio valley. The land was being eyed. So that when the territory was purchased in 1804, there was already a large population.

In 1804, as President Thomas Jefferson commissioned a Corps under the command of Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, the Morrison family would establish themselves on the Rue de Grande, later known as Main Street, in St. Charles. The family had been on the leading edge coming from Philadelphia and had already established outposts for trade in Cincinnati and Kaskaskia. William Morrison, and his younger brother Jesse, were cousins to the Boone family, through Daniel’s wife, the former Rebecca Bryan, and would establish Bryan and Morrison at the northern landing on the Missouri River. A pathway had already been established from Saint Louis to Saint Charles, which was referred to as the St. Charles Road. However, it was salt lick referred owned by the Morrisons in partnership with Daniel Boone’s sons Nathan and Daniel Morgan, that gave its name to the region further west, the Boone’s lick.

Salt was one of the most valuable commodities necessary in 1804. Needed not only for curing and preserving their meat but used in tanning furs as well. The beaver, bear and buffalo furs were rendered not only into the fashions of the time but worn by all. Salt was manufactured by boiling water originating from a saltwater spring, a tedious, difficult and often dangerous process. The Bryan and Morrison salt lick had been discovered by the Boone family earlier and was the largest in its’ day. Made even more successful by the generous funds of the Morrison family and the large workforce, many of which were enslaved, that ran the factory 24 hours a day and seven days a week. The salt was packed in bags and crates; and carried downriver on the Missouri River to the landing and the huge stone storehouse to be sold at the Morrison’s mercantile. Supplies and manpower were then carted overland back up to the salt lick, using what became known as the Boone’s Lick trail. No longer just a trace used by the native populations, it was an established trail used by everyone to go westward.

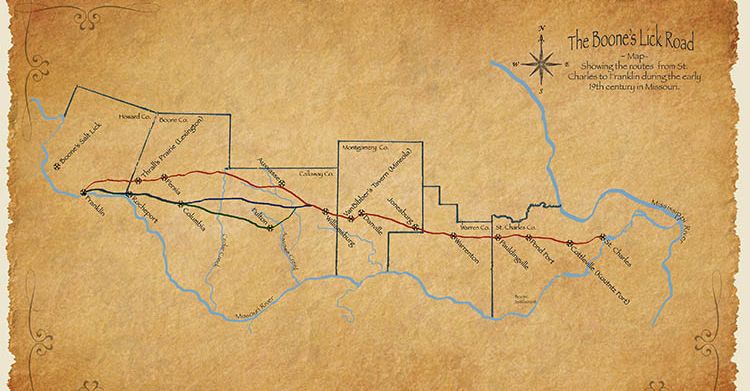

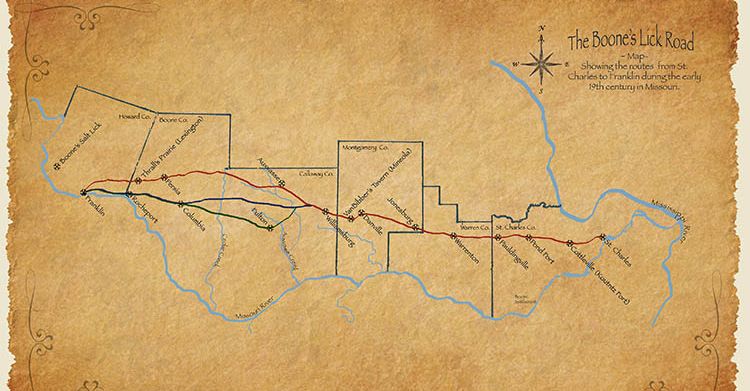

Documentation of the Boone’s Lick Road comes from many sources. Maps, plats and Surveys, showing early Spanish Land Grants (on an angle) establish when the property was purchased, with deeds going more in depth. Early deeds will quite often establish where the Boone’s Lick Road intersects with a property, or lines its’ border. Early journals are often simple notes, describing the road’s conditions or available lodging. A gazetteer is similar as it just simply gives the local’s name for a place and what is found at that location. Newspapers share postal routes and stagecoach stations, and the distances are helpful to a degree, as property owners and postmasters could often change. Early historians like Kate Gregg bring so much depth and history by adding details about the residents and their activities.]

A factory for trade had been established with the Osage, named Fort Osage, just west of the salt lick by 1808. The settlement of San Carlos with 100 families, as Lewis and Clark described it in 1804, was incorporated as the Village of St. Charles in 1809. Within a few years, its Territorial Governor Benjamin Howard, would raise two Corps of soldiers, led by both the Boone sons, to control the uprisings that were occurring between the settlers and the earliest residents. What was called the War of 1812 in the east, was simply referred to as the Indian Wars in the U.S.’ Louisiana Territory. The dispute over the control of what had been the native Americans, presided over the residents’ lives for several years, with several homes turned into fortresses, along the Boone’s Lick trail. This in turn established what had once been only a trace, into an actual road, by the end of the hostilities in 1815.

In 1816, residents along the road, would petition the young Territorial Government to establish this road. They wanted the road surveyed and marked so that everyone could follow it safely. Postal Routes were being established, and they needed the road marked, as competition among the earlier “forts” became Post Offices and Stagecoach stops. Settlement and westward travel were increasing, and the best routes brought the highest returns. By 1817, both Boone brothers had sold out their portion of the partnership to the Morrisons. By 1818, the population had increased tremendously with the end of the hostilities, and they had reached the threshold of 60,000 necessary for Statehood. Emissaries were sent to D.C. wanting admittance. However, as Congress debated the issue of slavery in what was to become Missouri, a debate raged in the territory as to where the Capitol was to become located.

It would take years, and a Compromise proposed by Kentucky’s statesman Henry Clay, before Missouri would become a state. And when the agreement was reached in 1821, it had been decided that the best location was with 50 miles of the Osage Nation, and along the Missouri River, in what was to become the City of Jefferson. However there not being any suitable building for the Capitol, a temporary location was needed. Saint Charles was chosen by the State’s Constitutional Commission which had been meeting in St Louis, as the location of Missouri’s First State Capitol. The building selected was Peck’s Mercantile, directly across Main Street from Morrison’s mercantile. And the road to reach Morrison’s salt lick and the City of Jefferson was by then called the Boone’s Lick Road. The termination of the road was in Howard County, the fastest growing county in the state, and was where the Santa Fe Trail began. The town of Franklin, in Howard County, in what was simply referred to as the Booneslick, had become the new frontier.

The Boone’s Lick Road had become the way west, with thousands using it, establishing Post Offices, then stagecoach stops, which turned from settlements to villages, and then to towns. What had once been simply a trace was now the “Big Road” and the way west.

The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) would work to mark the Boone’s Lick Road in 1913, giving us a tangible reminder and keeping the history of the road alive. Sometimes these markers have been moved or become lost as progress established new roadways. Some locations would not be known today if it were not for the DAR’s efforts to preserve the road’s history and the role it played in our state’s history. Research methodology did not have the availability of records that modern historians have today. These markers still provide a great tour for those who want to follow the road on their own and will be shared throughout this story. All DAR markers noted are taken from the following website: https://viewer.mapme.com/mssdarbooneslick/location/1a5b287e-3a03-4094-af86-fe6bdd1ba865/gallery/1%5D

When the French-Canadian fur trader, Louis Blanchette, settled along the Missouri River he would refer to his settlement as Les Petite Cotes or ‘the Little Hills’ in an area known for the mounds made by the indigenous people. In the Carte des Etats-Unis de L’Amerique dated 1784, neither they nor the settlement of Saint Louis are indicated. By 1800 it would become known as San Carlos, meaning St. Charles, with it being the terminus of a trail from Saint Louis, as there was no “Boon’s Lick” at that time. In May of 1804, Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark would make it their first stop, with their journals stating it had about 100 families living there. The ‘road’ west that they would travel was called the Missouri River.

FOR MORE INFORMATION SEE https://www.booneslickroad.org/

For more stories like this in your email box each day…

2 responses to “The Boone’s Lick Road”

I love reading your articles but this is meant to be humor, right? Only three settlements west of the Mississippi? Did you forget to add, “in Missouri?

LikeLike

Thank You Jake. I did!!

LikeLike